If you find yourself missing the 1990s, the government’s antitrust case against Google will bring you back to the bad old Microsoft days.

Donald Trump administration’s legal battle that has been unleashed on Google truly feels like a blast from the past.

The U.S. Justice Department filed an equally high-profile case against a technology giant in 1998, accusing it of leveraging a monopoly position to lock customers into its products so they wouldn’t be tempted by potentially superior options from smaller rivals.

Table of contents

Target: Microsoft

That game-changing case, of course, targeted Microsoft and its personal computer software empire — right around the same time that two ambitious entrepreneurs, both strident Microsoft critics, were starting up their own company with a funny name: Google.

Now things have come full circle with a lawsuit that deliberately echoes the U.S.-Microsoft showdown that unfolded under the administrations of President Bill Clinton and President George W. Bush.

“Back then, Google claimed Microsoft’s practices were anticompetitive, and yet, now, Google deploys the same playbook to sustain its own monopolies,” the Justice Department wrote in its lawsuit, filed Tuesday in Washington, D.C., federal court.

The Complaint

The Justice Department’s 64-page complaint accuses Google of thwarting competition and potential innovation via its market power and financial muscle. In particular, the U.S. complaint alleges, Google sought to ensure its search engine and advertising network remained in a position to reach as many people as possible while making it nearly impossible for viable challengers to emerge.

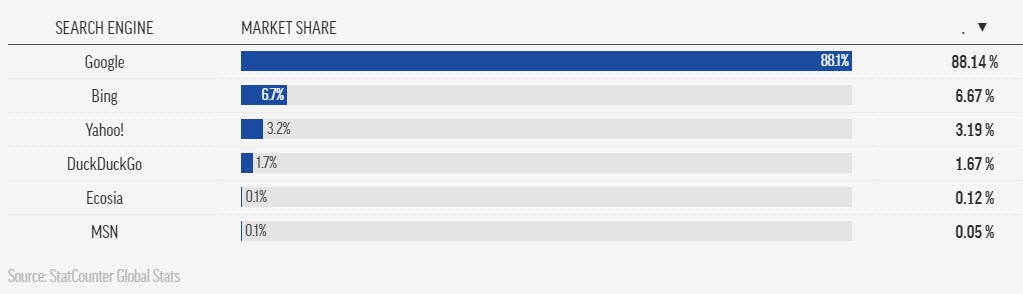

U.S. Deputy Attorney General Jeff Rosen described Google as “the gateway to the internet” and a search advertising behemoth. Google, whose corporate parent Alphabet Inc. has a market value just over $1 trillion, controls about 90% of global web searches.

The Mountain View, California, company, vehemently denied any wrongdoing and defended its services as a boon for consumers — a position it said it will fiercely defend in a case that seems likely to culminate in a trial late next year or sometime in 2022.

Eleven States

Eleven states, all with Republican attorneys general, joined the federal government in the lawsuit. But several other states demurred.

That dynamic raised questions about whether the timing of the government’s move is politically motivated, given that Election Day is less than two weeks away. President Donald Trump has also repeatedly attacked Google with unfounded charges that it is biased against conservative viewpoints in its search results and posted on its YouTube video site.

To avoid the appearance of political animus, Justice Department officials were under intense pressure to present a strong case against Google. Some legal experts believe regulators pulled that off.

Strongest Suit

The Justice Department “filed the strongest suit they have,” said antitrust expert Tim Wu, a professor at Columbia University Law School. But he also believes the suit is almost a carbon copy of the government’s 1998 lawsuit against Microsoft.

Wu believes the U.S. government has a decent chance of winning. “However, the likely remedies — i.e., knock it off, no more making Google the default — are not particularly likely to transform the broader tech ecosystem.” he said via email.

Investors Bet On Google

Investors so far are betting Google will prevail — or at least that its business won’t be fazed by its tussle with the U.S. government. Alphabet’s stock rose more than 1% Tuesday to close at $1.555.93. As of Wednesday afternoon, it’s stock rose to 1,609.19.

The Justice Department is primarily targeting Google for negotiating lucrative deals with the makers of smartphones and web browsers to make its search engine the default option unless consumers take the trouble to change the built-in settings. The company also ensured the search engine would be built into the billions of phones powered by its Android operating system by making that a requirement to use the app store accompanying the free software.

The 1990s case against Microsoft followed a similar premise. Regulators then accused the company of forcing PC makers reliant on its dominant Windows operating system to also feature Microsoft’s Explorer web browser — right as the internet was starting to go mainstream. That bundling crushed a once more-popular browser, Netscape.

Google contends the Justice Department is relying on “deeply flawed” theories that have become outdated by dramatic changes in technology. The company hammered home that point in a Tuesday presentation with reporters that proclaimed, “This isn’t the 1990s.”

Could Smartphones Save Google?

Perhaps the most significant change has been the explosion of smartphone apps that make it fairly simple to for consumers to pick and choose the services they want to use. Google says users of Android phones, typically have about 50 apps on them.

Google also maintains that the same deals that make its search engine ubiquitous also benefits consumers by boosting the fortunes of its partners. For instance, the company argues its free Android software and its search-engine deal with Apple — worth an estimated $8 billion to $12 billion annually — help hold down the prices of smartphones.

Back in 2001, Microsoft appeared to escape the worst outcome. Initially, after a dramatic court trial, a federal judge ruled that the company should be broken up. But that never happened. Instead, the two sides reached a settlement in 2002 that placed restrictions preventing Microsoft from bundling its products so brazenly.

By the time that consent decree expired in 2011, distractions caused by the antitrust case had contributed to Microsoft business miscalculations and the apparent blunting of the company’s aggressive instincts. Microsoft ultimately proved unable to accurately assess the impact of internet search and the shift to smartphones, forcing it to play a long and ultimately fruitless game of catch-up.

Coincidentally or not, that was also right around the time that Microsoft began to complain to U.S. regulators about Google’s anticompetitive practices.

Most Important Takeaways From Google Antitrust Lawsuit

The Justice Department’s lawsuit against Google alleging antitrust violations marks the government’s most significant attempt to protect competition since its groundbreaking case against Microsoft more than 20 years ago. The lawsuit claims Google has abused its dominance in online search and advertising to stifle competition and harm consumers.

What You Need To Know About the Lawsuit, and It’s Effect On You.

What is really happening here?

This is one step against a single company. But it is also a response to the policy question of what measures, if any, should be taken to curb today’s tech giants, which hold the power to shape markets, communication and even public opinion.Politics steered the timing and shape of this suit. Attorney General William P. Barr wanted to move quickly to take action before the election, making good on President Trump’s pledge to take on Big Tech. Eleven states joined the suit.

U.S. Says Google Has Become A Monopoly

After years of hemming and hawing over the matter, the U.S. government has now formally described Google as an illegal monopolist.

Just being a monopolist isn’t illegal. And that’s been good for Google, since it dominates roughly 90% of the market for internet searches. But abuse of monopoly can easily land a company in trouble.

The Justice Department went there, calling Google a “monopoly gatekeeper for the internet” that has used “anticompetitive tactics” to maintain and extend monopolies in both search and search ads. The lawsuit alleges that Google stifled competition and innovation from smaller upstarts and harmed consumers by reducing the quality and variety of search options — and that the company also uses its monopoly money to lock in its favorable position on smartphones and in browsers.

Google Says That Free Is Good

Unsurprisingly, Google sees this differently. The company argues that its services are useful and beneficial to consumers, that they face ample competition and that they’ve unleashed innovations that help people manage their lives.

What’s more, those services are free for consumers to use, at least in monetary terms. What Google doesn’t often remind its users is that it’s handsomely reimbursed by all the search ads it runs on behalf of outside advertisers, which it targets using the personal information its users hand over, often unknowingly, while taking advantage of its “free” services.

Google also emphasizes that its services hold down the cost of smartphones and that its lucrative exclusive deals to make Google Search the default on many phones — what the government calls its “exclusionary agreements” — don’t stop users from changing to rival search engines if they want to.

IS THIS ALL ABOUT POLITICS?

From the timing of the case to its co-plaintiffs, the Justice Department’s lawsuit raises unanswered questions about the politics behind the move. For starters, there’s the fact that it filed the suit exactly two weeks before Election Day, a time when most administrations generally try to avoid making splashy moves for fear of being seen as attempting to influence elections.

It also did so in conjunction with just 11 states, all of whom have Republican attorneys general, despite the fact that all 50 states kicked off an investigation of Google roughly a year ago.

The attorneys general of New York, Colorado, Iowa, Nebraska, North Carolina, Tennessee and Utah released a statement Monday saying they have not concluded their investigation into Google and would want to consolidate their case with the Justice Department’s if they decide to file.

Did Google Turn Into Microsoft?

The case against Google bears a strong resemblance to one the government brought 22 years ago against the Goliath of the time: Microsoft. But Google’s days as the fledgling startup looking to “do no evil” are long behind it.

Back then, Google cast itself as the underdog fighting against a technological bully. The Justice Department’s Google case today revolves around the company bundling products around its dominant position in search — much like the 1998 case against Microsoft revolved around its bundling of other products around Windows.

Tuesday’s lawsuit notes that back then, Google claimed Microsoft’s practices were anticompetitive, “and yet now, Google deploys the same playbook to sustain its own monopolies.”

Google sniped back in its own response to the lawsuit. “This isn’t the dial-up 1990s, when changing services was slow and difficult, and often required you to buy and install software with a CD-ROM,” the company said in a blog post. “Today, you can easily download your choice of apps or change your default settings in a matter of seconds.”

Advertisers Have Become the Victims?

Google will hold more than 29% of the U.S. digital advertising market by the end of this year, with Facebook following second with 24% and Amazon third, according to research firm eMarketer. But that’s all digital ads — in search ads only, Google is by far the heavy, holding nearly three-quarters of the market.

This, the DOJ argues, unfairly shuts out any would-be competitors, and can leave advertisers themselves with subpar service and few alternatives.

The lawsuit charges that Google’s “exclusionary” conduct stifles competition in search advertising, thus harming advertisers. By suppressing competition, Google has more power to manipulate the “quantity of ad inventory auction dynamics” — that is, how much advertisers pay for their ads — in ways that allow the company to charge advertisers more than it could in a competitive market, the lawsuit says.

Plus, Google can also offer businesses lower-quality ad services if it wants to, the lawsuit argues — for instance, by restricting the information it provides them on their own marketing campaigns. Without viable competition, who’s to stop it?

What will be Google’s defense?

In short: We’re not dominant, and competition on the internet is just “one click away.”

That is the essence of recent testimony in Congress by Google executives. Google’s share of the search market in the United States is about 80 percent. But looking only at the market for “general” search, the company says, is myopic. Nearly half of online shopping searches, it notes, begin on Amazon.

Next, Google says the deals the Justice Department is citing are entirely legal. Such company-to-company deals violate antitrust law only if they can be shown to exclude competition. Users can freely switch to other search engines, like Microsoft’s Bing or Yahoo Search, anytime they want, Google insists. Its search service, Google says, is the runaway market leader because people prefer it.

What happens next?

Unless the government and Google reach a settlement, they’re headed to court. Trials and appeals in such cases can take years.

Whatever the outcome, one thing is certain: Google will face continued scrutiny for a long time.