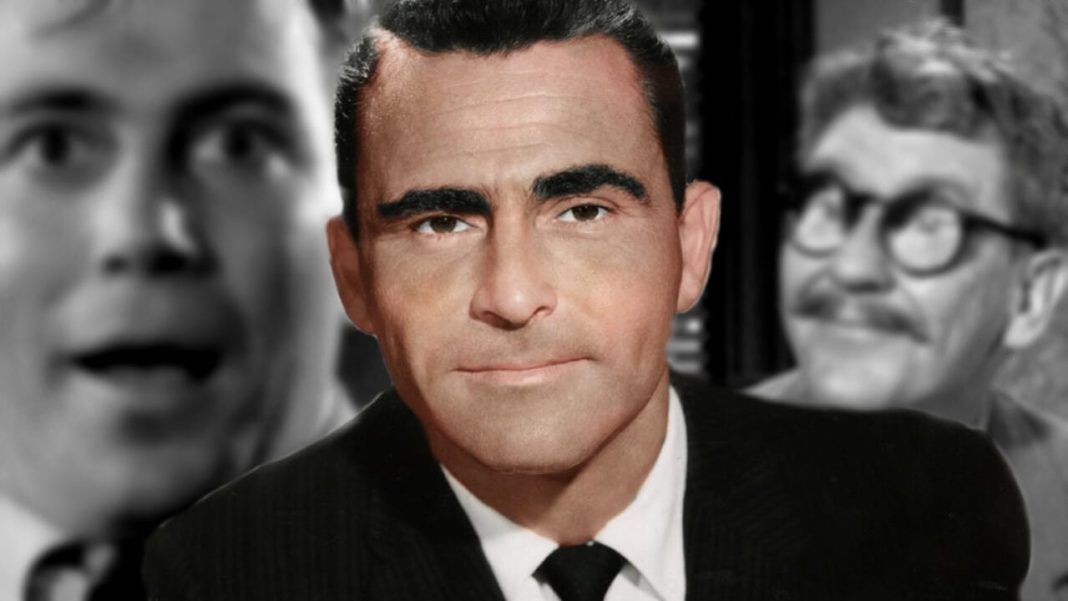

SyFy’s annual “The Twilight Zone” marathon brings us back to the late 1940s and early 1950s, an era dominated by TV shows depicting ideal families and neighborhoods, like “Leave it to Beaver.” However, Rod Serling’s “The Twilight Zone” revolutionized TV by exploring paranormal themes and addressing real societal issues.

Unlike its predecessors, “The Twilight Zone” delved into the realms of the strange and unusual. It was a show that dared to explore the paranormal, weaving tales of time travel, telepathy, and even pacts with the devil. At first glance, it might seem like Serling’s creation was a leap further away from reality compared to the idealistic world of “Leave it to Beaver.” However, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that “The Twilight Zone” was more than just a series about the supernatural; it was a platform for addressing very real and pressing issues.

Serling’s Idyllic Childhood

Rod Serling had that perfect idyllic childhood presented by many of the shows of that day. But like many of us, he entered the read world to discover the harsh cold reality of life.

Rodman Edward Serling was a Christmas baby born in Syracuse, New York, on December 25, 1924. He was the unexpected joy in the lives of his parents, Sam and Esther Serling, a grocer and a homemaker. Rod quickly became the apple of their eye, especially since his arrival was a bit of a miracle after doctors had told his mom she couldn’t have more kids.

Rod, the younger of two boys, was the life of the party in the family, always full of energy and laughter. This was quite the opposite of his older brother Robert, who was more on the reserved side.

In 1926, the Serling family packed up and moved to Binghamton, New York, a place that Rod would later fondly remember as the backdrop of his childhood. He often said, “Everybody has a hometown,” and for him, Binghamton was that special place, a safe haven he would revisit in his thoughts and in his writings. You can see this nostalgia in some of his famous Twilight Zone episodes like “Walking Distance” and “A Stop at Willoughby.”

Rod was a bundle of energy and competitiveness, especially when it came to sports. During his time at Binghamton Central High School, he had his heart set on being the quarterback for the football team. But fate had other plans – he was just a bit too light to make the cut. Rod, with his ever-present humor, would later joke about being lighter than the team mascot!

Not one to be easily discouraged, Rod threw himself into other sports like intramural football and tennis, where he played with a fiery spirit. His high school buddy, Sybil Goldenberg, said his determination was twice as strong because he was on the shorter side. And speaking of height, Rod was always a bit self-conscious about being 5 feet 4 and a half inches tall, even wearing lifts and preferring not to be filmed in full frame for his Twilight Zone intros.

But where Rod really stood tall was in the world of words. He was a star on his high school debate team, known for his quick wit and clever comebacks. He dived into school politics too, eventually becoming the president of the General Organization and the editor of the school newspaper. His fiery editorials in the paper were just a hint of the passionate advocate for social justice he would become.

Fighting CBS and 1950s Censorship

What was most interesting was that Serling was able to use science fiction as a way to skirt all the issues of censorship that began surfacing in the late 1950s…much like today’s world. He had to fight hard with the CBS network when the executives insisted on editing his (what they consider to be) very controversial scripts.

CBS often won the censorship war with Serling such as his piece about lynching which was called “A Town Has Turned to Dust” along with “The Rank and File” about labor union corruption. Rather than continue the losing fight, he switched over to the sci-fi fantasy genre in 1959 and found himself able to write freely. The network didn’t pay as much attention to his scripts for “The Twilight Zone,” giving Serling more creative freedom than he had ever had there. He wound up writing 92 episodes of the 156-episode series.

Rod Serling’s journey to creating this iconic show was as intriguing as the show itself. Born in Binghamton, New York, a city that remarkably skirted the harsh impacts of the Great Depression, Serling grew up in a relatively comfortable environment. His father owned a successful grocery store, allowing the family to live a life that closely resembled the blissful images portrayed in early television shows. However, Serling’s brush with the harsh realities of life came at the tender age of 18.

Serling’s War

Like many young men of his generation, Serling was compelled to enlist in the army following the attack on Pearl Harbor. As a Jewish man, he felt a strong urge to fight against the Nazis during World War II, but fate had other plans, and he found himself in the Pacific War, battling against Japan. It was during the Battle of Leyte in 1944 that Serling’s life changed forever. He sustained injuries to his wrist and knee from bomb shrapnel, earning him a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star. But the scars of war ran deeper than his physical wounds.

Upon his return from the war, Serling found himself relentlessly pursued by the specters of his past, his mind a battleground scarred by nightmares and flashbacks. Among these haunting memories, one harrowing incident during World War II stood out, a moment that would forever alter the course of his life and the essence of his creative work. It was amidst the chaos of the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Pacific, a brief respite twisted into a scene of horror.

As Serling and a comrade shared a moment, capturing it in a photograph, fate struck a cruel blow. From the skies, an Air Force plane unwittingly unleashed a deadly cargo – a box of extra ammunition. It plummeted to the earth with tragic precision, striking Serling’s friend, crushing him under its brutal weight. This gruesome and fateful moment would not only scar Serling’s memory but also ignite a dark spark of inspiration, weaving its way through the tapestry of his scripts and stories, forever etched in his haunted narrative.

His daughter, Anne Serling, recalls her father being tormented by nightmares of the war, a clear indication of the post-traumatic stress he suffered. This is a plight all too common among veterans, with a staggering 47% not receiving the necessary support for their PTSD. Fortunately for Serling, he found solace and a means to process his trauma through his writing.

Before The Twilight Zone

Before creating “The Twilight Zone,” Serling worked on various TV shows, including “Lux Video Theatre” and “Studio One.” These early works sometimes touched upon themes of war and the paranormal, setting the stage for what was to come. In 1959, “The Twilight Zone” was born, a series that is often remembered for its exploration of the bizarre and eerie. However, Serling’s primary goal wasn’t just to thrill and chill his audience; he used the paranormal as a lens to discuss broader societal issues such as prejudice, brutality, and the horrors of warfare.

Episodes like “He’s Alive,” where the ghost of Hitler inspires an American neo-Nazi, and “I Am the Night—Color Me Black,” which explores the consequences of hatred and injustice, are prime examples of how Serling used the show to comment on the persistent issues of bigotry and moral decay. A significant portion of “The Twilight Zone” episodes also focused on war, reflecting Serling’s own traumatic experiences. “A Quality of Mercy,” for instance, is a poignant story about an American GI and a Japanese soldier swapping bodies, offering a powerful critique of the senselessness and cruelty of war.

In essence, “The Twilight Zone,” while famous for its foray into the fantastical, was Rod Serling’s way of grappling with his own demons and shedding light on the darker aspects of reality that often go unspoken. Through his genius storytelling, Serling not only entertained but also enlightened his audience, leaving a legacy that continues to resonate with viewers to this day. Top of Form

Rod Serling’s Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes

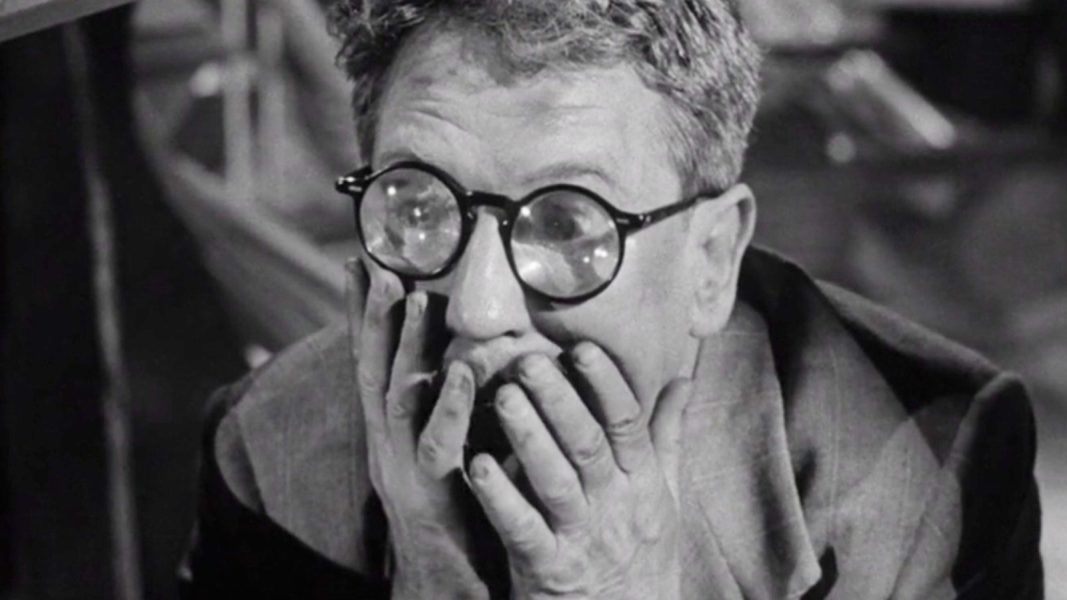

Have you ever wondered which “Twilight Zone” episodes Rod Serling himself loved the most? I certainly did and it turns out, he had two favorites. The first one? “Time Enough at Last.” It’s the eighth episode and an absolute classic. It’s like the show hit its peak super early. But, you know, while “Time Enough at Last” is a standout, it paved the way for more amazing episodes.

The episode stars Burgess Meredith, you know, the guy from “Rocky” and “Of Mice and Men.” He plays Henry Bemis, this super mild-mannered bank teller who’s just not getting any love from his boss or, even worse, his wife. Poor Bemis isn’t a bad guy; he’s just super into his books, and that’s his happy place. But everyone around him just doesn’t get it and gives him a hard time for it.

Serling’s take on Lynn Venable’s short story hones in on Bemis’s tough situation. Watching Meredith, with his thick glasses and his kind of awkward way of speaking, you can’t help but feel for the guy. He’s a dreamer surrounded by nightmares, judged way too harshly. They’re always on his case, messing with his books. All we want is for Bemis to have his moment with his books. He totally deserves it.

Then, boom, the apocalypse hits, and suddenly, Bemis is the last man on Earth. Lucky for him, he was in the bank vault when it all went down. Now, with no one to bug him and a mostly intact library, he’s got all the time in the world to read. Perfect, right?

But then, tragedy strikes. His glasses break. All those books, and he can’t read a single one. Bemis is devastated, and we’re left with one of the most memorable moments in TV history.

Twilight Zone’s Iconic Twists

A lot of “Twilight Zone” episodes have this ironic, tragic twist, but usually, the characters kind of had it coming. Like the astronaut in “I Shot An Arrow Into the Sky” or the conspiracy theorist in “Four O’Clock.” But Bemis? He did nothing to deserve such a sad ending. Life was tough on him, and then, when he finally got a break, fate (or the Twilight Zone) had other plans.

In a 1970 chat with sci-fi writer James Gunn (not the “Guardians of the Galaxy” guy), Serling shared that “Time Enough at Last” was one of his top picks. He loved the irony of it all and was pretty proud of how they pulled it off with a TV budget, using an MGM backlot to make it look like a movie.

His other favorite, “The Invaders,” with Agnes Moorehead fighting tiny aliens, didn’t fare as well in the special effects department. Serling wished they could’ve done more, but hey, it was the ’60s, and TV had its limits. They had to work with what they had, even if it meant using not-so-convincing rubber aliens.

So, yeah, for Serling, “Time Enough at Last” was a big win, even if it wasn’t such a happy ending for Mr. Bemis.

The Twilight Zone Helps Shape Mental Illness Perceptions

The original “Twilight Zone” series, a seminal television program from the late 1950s and early 1960s, utilized themes of mental distress as a critical lens to examine American cultural norms of the era, particularly the emphasis on unwavering rationality, social conformity, and the prioritization of work in daily life. This exploration was not merely metaphorical; it also challenged the prevailing notion of mental soundness as a mandatory standard, highlighting its potential perils for both individuals and society at large.

Episodes such as “Mirror Image,” “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” and “The Arrival” feature protagonists who confront inexplicable phenomena, compelling them to reassess their conventional, rational perspectives to make sense of their experiences. This narrative device underscores the idea that perceptions of madness are socially constructed. Furthermore, the scrutiny these characters face for deviating from middle-class American behavioral norms underscores the enforced expectation of mental soundness.

During the era of “The Twilight Zone,” American perspectives on mental health were evolving significantly. The deinstitutionalization movement was reintegrating mental health patients into society, while psychoanalytic theories intersected with emerging preventative medical practices. This convergence fostered a belief in an inherent, latent madness within all individuals, which responsible citizens were expected to control. The series frequently depicted asylums, with several episodes concluding with the protagonists being involuntarily committed for failing to adhere to societal expectations of mental stability in the face of unexplainable events.

Through its portrayal of mental distress, “The Twilight Zone” was able to shed light on the inhumane treatment of mental health patients in mid-20th century America. It encouraged viewers to consider unconventional, non-normative, or even ‘mad’ approaches as viable alternatives to the prevailing social norms.

Art As Therapy

Rod Serling masterfully demonstrated the power of art as a tool for navigating life’s challenges. His iconic work in “The Twilight Zone” resonates with audiences even today, addressing timeless issues that continue to be relevant. Serling skillfully channeled his experiences with PTSD into his art, bringing attention to a subject that was scarcely discussed at the time, while also confronting his personal traumas from the war. This exemplifies how art can be a therapeutic medium for many. Regrettably, the decline of art programs in schools has limited this vital outlet for those who might benefit from it most.