Even if you’re not the most political person out there, you know that the next several months will be a barrage of ads from 2016 Presidential election candidate hopefuls. Each week we’ll hear of a new poll that has come out declaring yet another time Donald Trump is victorious again. Then we’ll hear more polls from the Democratic side speaking of Bernie Sanders either being a solid communist (the New York Post loves to declare this every few weeks) or solidly ahead of Hillary Clinton.

As with most polls that should be taken out of some of these candidates rear ends, they are selective and don’t always give the full story. The media latches onto them for ratings and makes Americans think that so and so is going to be your next President of the United States.

Our friends at Predict Wise have come up with one chart guaranteed (maybe, maybe not) to show who our next President will be in 2016.

Just about every morning, a major media outlet announces the results of a new presidential poll. “Donald Trump dominates first national poll of 2016.” “Cruz surges to top in California.” These articles often go on to analyze every minor shift and hidden trend in the data, proclaiming one candidate’s death and another candidate’s resurgence.

The problem? Polls like these mean next to nothing.

Yes, the survey methodologies are sound, the margins of error properly noted. But presidential primary polling — especially, the national polls — do very little to actually predict who will win the nomination.

How can we get a better sense of who will win in November? The answer is prediction markets.

Prediction markets don’t follow poll results — they follow the money. Every time someone bets a certain candidate will win (typically, through an online bookie or in Las Vegas), prediction markets record that bet. Over time, these markets make a prediction based on tens of thousands of bets. For example, here is how the markets see the GOP nomination race, as aggregated by Predict Wise.

Note: PredictWise does include polling as part of the overall percentage, but draws most heavily from the prediction markets.

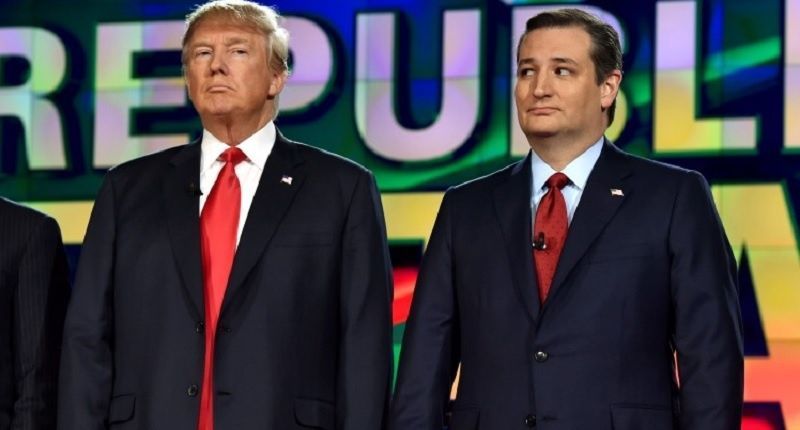

The national polls see Donald Trump as the heavy favorite, but the markets peg his chances at only about 34 percent, just a bit above Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and on par with Florida Sen. Marco Rubio. The markets give former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie an outside shot while pegging everyone else’s chances at virtually 0 percent.

The markets are smart because the people making the bets are smart. Most serious sports gamblers are sports fanatics, with intimate knowledge of teams, coaches, and players. The same is true for political bettors, who often know how to account for historical trends, likely candidate weaknesses, establishment support and state-specific voting demographics. Critically, they’re also betting their own money, rather than responding offhand to a phone or online poll, providing, even more, incentive to make the right pick.

Compare the betting market visualization to the RealClearPolitics aggregation of national polls.

Here, we see where all those headlines are coming from, with Trump dominating the field and Cruz comfortably in second.

What exactly is wrong with the national polls? The first issue: Most of these survey the entire nation, yet there is no such thing as a national primary. In reality, states vote individually. This gives lesser-known or unique candidates a better chance in certain states. For example, very conservative candidates like former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee and former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum performed well in Iowa in previous cycles, despite performing worse in national polls. What’s more, each state’s results influence the next state. By the time California or Texas votes, most of the candidates will have dropped out, and momentum will have changed considerably.

Consider that former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani led national polls for months in 2007, and then failed to win a single state in 2008. Or look at Secretary of State John Kerry, who lingered in the single digits for most of 2003, only to notch a surprise Iowa victory and cruise along to the Democratic nomination in 2004. In each case, national polls were not only off the mark but downright misleading.

The second issue: National polls tend to be heavily influenced by name recognition, trendy stories in the press and a handful of unlikely voters. On the day of the caucus or primary, a smaller group of more engaged individuals will do the actual voting. And we’re not just talking about surveys conducted six months before the Iowa caucuses. Even late-January polls tend to fall victim to this same bias.

Individual state polls do a better job predicting winners, but even these can’t predict the eventual nominee. For example, Cruz looks likely to win Iowa, but he remains a distant third in New Hampshire. Will a win in Iowa give him enough momentum to overcome a 20-point deficit in later states? Will a single second-place finish doom Trump’s “winning” brand? Even if we correctly guess who wins the first three or four states, predicting the next 20 is a much murkier proposition.

Some publications have caught on. In its presidential campaign dashboard, the New York Times ignores national polling and lists prediction markets as its No. 1 metric for “Who’s Winning the Presidential Campaign.” In general, however, there are still far more headlines about minor national polling updates, rather than reports on the general trends found in prediction markets.

Naturally, prediction markets aren’t perfect. Casual bettors can influence the markets, and trendy stories can still affect where people place their bets (just not as significantly as they affect day-to-day polling). For example, note how Rubio soared to a 48 percent chance in late November, then settled back to the 30s by January. While we won’t be able to grade the markets until the primaries conclude, that 48 percent spike likely was a market overreaction, given the volatile state of the race.

Still, prediction markets tend to look calm and sensible next to polling results. When markets make mistakes — like overvaluing Bush or Rubio’s chances — they tend to correct themselves before the final votes are cast. And they rarely spike or dive out of nowhere, preferring instead to gently adjust to changing realities. Compare the gradual corrections in the prediction markets to the weekly swings of national polling averages, which tend to look even more ridiculous once the results are in.

In fairness, national polling can be helpful, even if it isn’t terribly predictive. In 2012, national polling helped propel a parade of Mitt Romney rivals, like Rick Perry, Herman Cain, Newt Gingrich and Santorum each earned a few weeks in the limelight. Post-2016, we’ll likely remember retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson and his three-month stint near the top of the polls, even if it ends up coming to nothing.

National primary polls can tell us a lot. They give us a snapshot of the race, help insurgent candidates rise (if only briefly) and provide a historical perspective on who shaped the political culture of the day. They just can’t tell us who is going to win.

If you’d still rather rely on national polling — and not the prediction markets — to pick the ultimate winner, that’s fine. Every year is different, and perhaps the national primary polls will be proven right. But before you assume the next polling headline is the most reliable picture of the race, ask yourself: Would you bet on it?