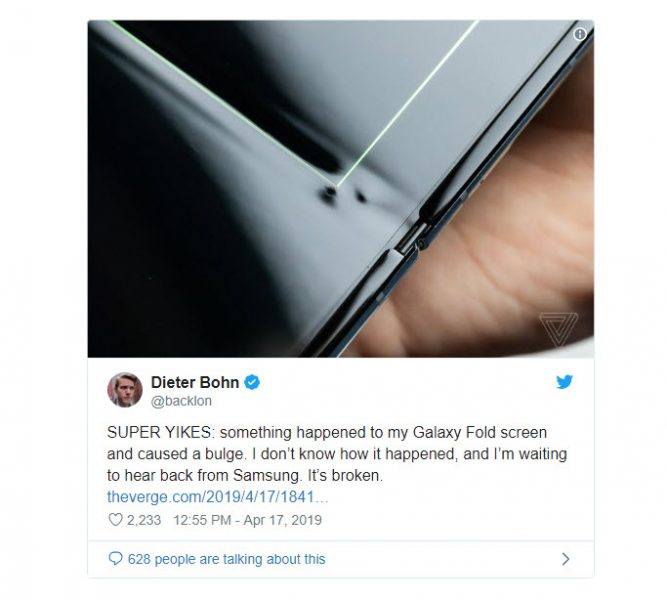

Samsung might be feeling a little 2016 deja vu with their Galaxy Fold that’s already being reported to break by some people. While it doesn’t officially go on sale until April 26, 2019, you can be sure they’ll be jumping on this quickly. Thankfully, no one has experienced an exploding battery as with the Galaxy Note 7 back then, but when a company is touting a smartphone or ‘phablet’ that you can fold, it better not break along that fold.

Some of Samsung’s new, almost $2,000 folding phones appear to be breaking after just a couple of days.

Journalists who received the phones to review before the public launch said the Galaxy Fold screen started flickering and turning black before completely fizzling out. Two journalists said they removed a thin, protective layer from the screens that they thought was supposed to come off, but was meant to stay.

But reporters from The Verge and CNBC said they left that layer on and their screens still broke. A CNBC video shows the left side of the inside screen intermittently flashing, and the right side as unresponsive.

The phone was “completely unusable” after two days, CNBC reporter Todd Haselton wrote.

The long-anticipated folding phone is about the size of a standard smartphone when folded, but can open up to the size of a small tablet. The phone is designed to work whether closed or open; when open, the single screen display is bisected by a crease.

Samsung promises the screen can withstand being opened and closed 200,000 times, or 100 times a day for five years.

The Galaxy Fold goes on sale April 26 in the U.S. for $1,980, making it one of the most expensive phones anywhere — particularly if it isn’t as durable as promised.

Samsung acknowledged it had heard reports of the screens breaking and said it would “thoroughly inspect these units in person to determine the cause of the matter.”

A company spokesman also said it would make it clear that the top protective layer is necessary to prevent scratches.

The company had a disastrous rollout of a new phone in 2016 with the Galaxy Note 7, which Samsung eventually recalled because its batteries were catching on fire.

Amazon, Google End YouTube Feud

Amazon and Google are ending their nearly 2-year spat, agreeing to bring their video streaming apps to each other’s devices.

Back in 2017, Google pulled its popular YouTube video app from Amazon’s Fire TV after the online shopping giant refused to sell some Google products. Amazon has since started to sell Google’s gadgets on its site.

Amazon said Thursday that YouTube will appear on Amazon’s Fire TV devices and smart TVs in the coming months, but did not give an exact date. Other YouTube apps, such as YouTube Kids and YouTube TV, will be added to Fire TV devices later this year. In addition, Amazon’s Prime Video streaming app will be added to Google’s streaming devices and TV’s that use Google’s operating system.

“We are excited to work with Amazon,” said Heather Rivera, YouTube’s global head of product partnerships, in a written statement.

Zoom, Pinterest Rack Up On Stock Market

Investors are giving unicorn technology companies Zoom and Pinterest a rousing reception in their debuts on the stock market.

Zoom Video Communications, which makes video conferencing technology, soared 81% when it opened for trading after pricing its initial public offering at $36. Pinterest, which lets users share images of crafts and other projects, jumped 25% after pricing its IPO at $19.

The high-flying market debuts come less than a month after ride-hailing service Lyft began trading. In what might be a cautionary tale for other anticipated tech IPOs, Lyft shares surged on their first day but have since plunged back below their original offering price.

Other high-profile companies such as Twitter and Snap had strong initial trading days but then saw their stock prices fall substantially in the subsequent months. Then again, there are companies like payment processor Square, which public at $9 per share, rose 45% on the first day of trading and now sell for around $70.

San Francisco-based Pinterest is on track to raise more than $1.4 billion on its first day of trading. The company has more than 250 million monthly users. Revenue, mainly through advertising, reached $736 million last year and the company posted a loss of $63 million.

Zoom, also based in San Francisco, is poised to raise more than $456 million through the sale of shares and a private placement. The company had $330 million in revenue last year and profit of $7.6 million, making it one of the few profitable technology companies going public this year.

Drones Helping Flooded United States

An arsenal of new technology is being put to the test fighting floods this year as rivers inundate towns and farm fields across the central United States. Drones, supercomputers and sonar that scans deep under water are helping to maintain flood control projects and predict just where rivers will roar out of their banks.

Together, these tools are putting detailed information to use in real time, enabling emergency managers and people at risk to make decisions that can save lives and property, said Kristie Franz, associate professor of geological and atmospheric sciences at Iowa State University.

The cost of this technology is coming down even as disaster recovery becomes more expensive, so “anything we can do to reduce the costs of these floods and natural hazards is worth it,” she said. “Of course, loss of life, which you can’t put a dollar amount on, is certainly worth that as well.”

U.S. scientists said in their spring weather outlook that 13 million people are at risk of major inundation, with more than 200 river gauges this week showing some level of flooding in the Mississippi River basin, which drains the vast middle of the United States. Major flooding continues in places from the Red River in North Dakota to near the mouth of the Mississippi in Louisiana, a map from the National Weather Service shows.

“There are over 200 million people that are under some elevated threat risk,” said Ed Clark, director of the National Water Center in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, a flood forecasting hub.

Much of the technology, such as the National Water Model , didn’t exist until recently. Fueled by supercomputers in Virginia and Florida, it came online about three years ago and expanded streamflow data by 700-fold, assembling data from 5 million river miles (8 million kilometers) of rivers and streams nationwide, including many smaller ones in remote areas.

“Our models simulate exactly what happens when the rain falls on the Earth and whether it runs off or infiltrates,” Clark said. “And so the current conditions, whether that be snow pack or the soil moisture in the snow pack, well that’s something we can measure and monitor and know.”

Emergency managers and dam safety officials can see simulations of the consequences of flood waters washing away a levee or crashing through a dam using technology developed at the University of Mississippi — a web-based system known as DSS-WISE . The software went online in 2017 and quickly provided simulations that informed the response to heavy rains that damaged spillways at the nation’s tallest dam in northern California. The program also helped forecast the flooding after Hurricane Harvey in Texas and Louisiana that year.

Engineers monitoring levees along the Mississippi River have been collecting and checking data using a geographic information system produced by Esri, said Nick Bidlack, levee safety program manager for the Memphis district of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The company produces mapping tools such as an interactive site showing the nation’s largest rivers and their average monthly flow.

On the Mississippi River, flood inspectors use smartphones or tablets in the field to input data into map-driven forms for water levels and the locations of inoperable flood gates, seepages, sand boils or levee slides, which are cracks or ditches in the slopes of an earthen levee. Photos, videos and other data are sent to an emergency flood operation center in real time, allowing Corps officials to visualize any problems and their exact location, instantly informing the response, Bidlack said.

“If people in the field have concerns about something, they can let us know to go out there and look at it,” Bidlack said. “There’s a picture associated with it, a description of it, and it helps us take care of it.”

Corps engineers are increasingly flying drones to get their own aerial photography and video of flooded areas they can’t otherwise get to because of high water or rough terrain, said Edward Dean, a Corps engineer.

“We can reach areas that are unreachable,” Dean said.

The Corps also now uses high-definition sonar in its daily operations to survey the riverbed, pinpointing where maintenance work needs to be done, said Corps engineer Andy Simmerman. The Memphis district uses a 26-foot survey boat called the Tiger Shark, with a sonar head that looks like an old-fashioned vacuum cleaner and collects millions of points per square inch of data, Simmerman said.

The technology has helped them find cars and trucks that have been dumped into the river, along with weak spots in the levees.

“These areas are 20 to 80 feet underwater, we’d never get to see them without sonar,” Simmerman said. “The water never gets low enough for us to see a lot of these failures.”

During recent flooding near Cairo, Illinois, a culvert that should have been closed was sending water onto the dry side of a levee. The sonar pointed engineers to the precise location of a log that was stuck 20 feet deep in murky water, keeping the culvert open. Plastic sheathing and sandbags were brought in to stop the flow and save the land below.

“The sonar definitely made a difference,” said Simmerman. “A big success.”