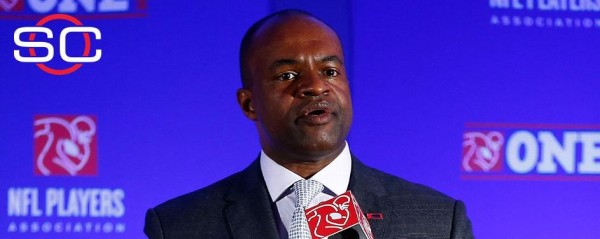

The NFLPA’s executive director had some interesting comments this week as he sat down with ESPN. He talked about his evolving role as head of the players’ union, the recent controversies in the League, the hypocrisy of punishments for players versus management, and of course his old buddy Roger Goodell.

I have never been a fan of the NFL Players Association, since they seem to get steam rolled in every negotiation. Any concession they get appears to be crumbs tossed to them by the team owners just to make these negotiations seem like a two sided “battle.”

This interview put DeMaurice Smith in a new light. Don’t get it twisted. I still know that the players union is no match for the NFL owners, but Smith makes some interesting points and clears up a few issues. Is Smith the right guy to keep as the head of the NFLPA? I can’t answer that, but I would guess that it doesn’t make a huge difference who leads the football players when the owners have such a big advantage when it comes to leverage.

Here are five highlights of Smith’s interview with Jim Trotter. The full interview is below.

5. Smith had this to say about the treatment of owners in regards to personal conduct, “When it comes to owner misconduct, the record is clear about the incidents that have caused players and fans to question the fairness of the system — in terms of how the Zygi Wilf and Jimmy Haslam and Jerry Jones and Jim Irsay situations were handled.” For anyone who knows how big companies work, this should not be very shocking. The higher up you go, the worse the stink. Roger Goodell is paid by the owners. How is he going to enforce any real punishments on his bosses? It would be akin to me making a citizen’s arrest on a cop running a stop sign.

4. Smith’s response to a question about using Goodell’s all-time low credibility to the union’s advantage: “I don’t believe it’s our job to “exploit” as much as it is to point out that the lack of credibility to the league office is something that all of us will suffer from.” I get where Smith is coming from here. If the commissioner looks like a slime ball then it is a bad look for the rest of the NFL. However, the union is in the best position ever to get Goodell to give up some more power. Maybe “exploit” isn’t the best word, but if I were Smith I would not let the public forget Goodell’s poor record of handing out punishments.

3. Smith says that the personal conduct policy is the last bastion of the commissioner’s sole power now that drug policy penalties and on the field fines are subject to being handled by neutral arbitration. I see no reason why Goodell should continue to be in full control of this aspect of league policy. He has a poor performance record so far and if he were a starting quarterback he would have been benched by now.

2. Smith stated, “Take the example of Aaron Hernandez: The Patriots refused to pay his workout bonus after he had been arrested, the union defended the process and the player because, according to his contract, he was due a workout bonus if he completed his workouts, which he had.” DeMaurice Smith is a lawyer and knows how it looks to defend a bad guy in the NFL, just like in the justice system. He makes it clear that the union’s job is to defend the collective bargaining agreement, even if it means getting compensation for a convicted killer like Hernandez. A team can’t just save some dollars when a player does something dumb if he held up his end of the contract up to that point. It would be like Tom Brady winning the Super Bowl, which may earn him a contract bonus of say $200,000, then hijacking a Greyhound bus the next day. If the Patriots tried to cheat him out of his bonus, that is unfair even though Tom should have never committed that crime. Regular Joes who get a DUI still get a paycheck from their job for hours they have already worked.

1. “We’re still in the same system we had when the commissioner was overturned in bounty, and then in Rice, and then in Peterson,” Smith said when talking about what it would take for Goodell to allow neutral arbitration concerning the personal conduct policy. It does appear that whenever an outside person make a ruling, Roger Goodell’s decision is overturned in some fashion. You would think the guy would want these decisions out of his hands by now with all the blow back he has received.

The main takeaway from the interview, regardless of your opinion of DeMaurice Smith, is Goodell’s reason for not wanting to give up any power. It is a childish reason. Roger Goodell just wants to have things his way and is a control freak, even to the detriment of his beloved League. The commissioner has proven he is not the best person to uphold the ever evolving personal conduct policy. Of course he has to be a big part of the process, but does not deserve to have the final say anymore.

ESPN.com: As a union, how do you approach these recent high-profile grievances between players and the league?

Smith: The fans and the media, they deal with every one of these things episodically. It’s Brady or it’s Peterson or it’s Rice or it’s McDonald. But we view these things philosophically — almost existentially — not episodically. Our job as a union is to defend our players. We wrap our hands around the player, we wrap our hands around the CBA, and anytime we believe the league violates the rights of either, this is what we do. So it’s not a, “Hey, are you guys going to defend Greg Hardy the same way that you defend a Tom Brady?” Well, yeah, this is what we do. This is what we do.

Is it about defending the process or defending the player?

Both. We have tried to negotiate these issues for literally decades. The first articulation of the commissioner’s power was in the first player contract, and over the decades we’ve negotiated scaling back that power to a more defined process. For example, in 2010 we came up with a new process that limited the commissioner’s power by subjecting it to neutral arbitration for on-field fines. And in 2011, we tried to negotiate that provision with respect to the drug policy, and the league refused for three years. It wasn’t until the last year that we scaled back the commissioner’s power by making his punishments subject to neutral arbitration under the drug policy. Really, the last step of this process is the personal conduct policy, and up until this point the league has been unwilling to make the same changes that they’ve made for on-field and drug policy applicable to the personal conduct policy.

The reason I mention the process vs. the player is that some people might take your words to mean that you condone the behavior or actions of the player.

I hear that. I guess because more of my training has been as a lawyer, when you are defending a person in the criminal justice system, I always view that as representing the person but ensuring that that person is entitled to fair process. These situations are no different. What the union finds philosophically and intellectually repugnant is when the league makes up rules as it goes along. That’s not only a violation of the player’s rights; it’s also a violation of the process as articulated by the collective bargaining agreement. And when they do that, it puts the union in the only position it can be in, and that is to respond.

In layman’s terms, how would you describe the role of the union?

It’s simply to enforce the rules of the collective bargaining agreement as it relates to protecting our players today and tomorrow. Take the example of Aaron Hernandez: The Patriots refused to pay his workout bonus after he had been arrested, the union defended the process and the player because, according to his contract, he was due a workout bonus if he completed his workouts, which he had. The union doesn’t ask the question of whether he got arrested for something or whether the league likes him or doesn’t like him, or whether the owner likes him or doesn’t like him. The union looks at the obligations of the league pursuant to the player’s contract, and if the team or the league violates that, we step in and we represent both the player and the process. When we believed that team doctors weren’t providing the best medical care according to generally accepted practices, we stepped in and raised the level of concern about pain-killing drugs. If a team doesn’t obey the concussion protocols, we seek to have sanctions against the team. If a team violates workout rules — even if the players in some cases may want to agree to it — we nonetheless step in and enforce the rule to protect the players. So when it comes to personal conduct, that’s not an anomaly. That’s an exercise in consistency.

What steps can be taken to get the commissioner to buy in on neutral arbitration under the personal conduct policy? Is the league showing any flexibility on that issue?

We certainly haven’t seen any flexibility from the league on that issue. The only thing that we can do is what we have done in previous negotiations, and that is to highlight why we believe neutral arbitration is good for both the players and the owners. Obviously, the league reached that conclusion when it came to on-field fines. Obviously, the league reached that conclusion when it came to issues arising from the drug policy. So, I’m at a loss as to why they don’t believe a neutral arbitrator isn’t in their best interest when it comes to the personal conduct policy. Because if anything has been clear — and both parties would agree — it’s that the last year was not a shining example of sound discretion by the commissioner. I’m not sure that any owner would want to look at last year and say, “That was a high point for the credibility of the owners and the credibility of the league to its fans, to its sponsors and to its players.” It’s hard to believe that three years after the [New Orleans Saints‘] bounty case, we’re still in the same system that lacks clarity. We’re still in the same system we had when the commissioner was overturned in bounty, and then in Rice, and then in Peterson.

Couldn’t one possible explanation be that the personal conduct policy isn’t being applied evenly to owners and players — that this is a means to keep the owners from being held to the same standards of conduct as the players? Does the union have any grounds or means to ensure that the policy is applied equally to owners as it is to players?

That is where truly the rubber meets the road. Frankly, the league has run out of logical excuses for why they resist a neutral arbitrator in the personal conduct policy. When you look at their public statements about the policy being applied fairly to both players and league personnel, you realize that is simply not true.

Not just that, but didn’t the commissioner say that owners and league employees would be held to a higher standard of conduct?

It’s clear to anyone who knows about all of the instances of misconduct that the policy isn’t being applied fairly. Accordingly, there’s no need to even guess whether league personnel are being held to a higher standard. That simply can’t be true. It’s clear to virtually everyone that there appears to be a lack of will on behalf of the league owners to have a policy that applies as equally to them as it does to the players.

Why do you think that is, at the risk of asking the obvious?

You’ll have to ask them. It’s obvious to everyone that there is a double standard. Right now, there doesn’t seem to be a majority of owners who want to do something about it. … When it comes to owner misconduct, the record is clear about the incidents that have caused players and fans to question the fairness of the system — in terms of how the Zygi Wilf and Jimmy Haslam and Jerry Jones and Jim Irsay situations were handled. I know that the league hired a new director of investigations; I’ll just assume that he hasn’t gotten to those [investigations] yet.

Earlier you brought up Roger’s credibility, and I think most people would agree it’s at an all-time low. Is there anything the union can do to exploit that for its own benefit?

Frankly, I don’t believe it’s our job to “exploit” as much as it is to point out that the lack of credibility to the league office is something that all of us will suffer from. Our goal is to have a league and its players and its owners in a position that warrants the respect of our fans and our business partners. If we all have a concern about that, it’s our duty, I believe, to make corrective measures. When it comes to the players, none of us wants a league where our sponsors lack faith in its integrity. That’s not good for the owners. That’s not good for the players.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but Goodell makes the argument that the commissioner’s office has always had this power and, therefore, he is not going to relinquish it. Is that accurate?

That’s his argument, but it’s a fallacy of incomplete. It is true that the personal conduct policy has been within the power of the commissioner, but the reality and the truth is that that power has not changed until it has changed. For example, the power of the commissioner to punish people for on-field violations rested within the power of the commissioner until it was changed in 2010. The power to discipline players under the drug policy rested with the commissioner until it was changed in 2014. So the reality is, the power vested within the commissioner under the personal conduct policy will remain that way until it is changed.

The obvious question is: What is going to precipitate that change?

The only thing that can precipitate a change is the exact same thing that has led to change in the past — and that is when both parties are committed to resolving their differences by collective bargaining. We have reached agreements on literally hundreds of issues since 1993 when we’ve done that.

If the players feel so strongly about neutral arbitration, why didn’t they stand up and fight for that in 2011 during the labor negotiations?

That was a subject of our negotiations, and the owners’ response was what their response is now: They’re not interested in changing the policy. That doesn’t mean, however, that the players should give up on the issue. The owners’ response to the drug policy in 2011 was that they did not want to change, and the players continued to negotiate that until we reached a resolution in 2014. One of the more powerful arguments for neutral arbitration and for a collectively bargained personal conduct policy is what happened last year. If there was ever an instance that demonstrated a need for a collectively bargained process, it’s a process that the NFL got wrong in Rice that led to it being overturned, that it got wrong in Peterson that led to it being overturned.

The union has asked the commissioner to recuse himself from hearing the Tom Brady appeal. Do you believe that part of the reason he has refused to do so is concern that he won’t get the ruling he wants, a la the bounty case when he appointed Paul Tagliabue to hear the appeal and the player suspensions were vacated?

Frankly, we don’t spend time trying to guess why league officials do or fail to do something. We focus on the facts. The former commissioner came in in bounty and overturned the decision of the commissioner. A neutral arbitrator jointly selected by the players and the league overturned the commissioner in Ray Rice. A federal district judge reviewed the arbitration of a current league employee and overturned the league in Mr. Peterson’s case. It seems from those facts that anytime someone who is distanced from the league reviews the league’s actions, it results in the commissioner being overturned.

Which would seem to indicate why the commissioner would not want to relinquish final say, right?

We let the facts speak for themselves.