Privacy rights advocates got a win on Friday after the Supreme Court ruled that police do need to get a warrant to look at records that reveal where cellphone users have been. Now law enforcement will require a judge’s approval before being able to track where you’ve been by way of historical cellphone location data. This decision upholds the Fourth Amendment which protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures.

The justices’ 5-4 decision marks a big change in how police may obtain information that phone companies collect from the ubiquitous cellphone towers that allow people to make and receive calls, and transmit data. The information has become an important tool in criminal investigations.

#Breaking: In a major privacy case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that police need a search warrant to track people through cell-phone tower searches.

— NPR (@NPR) June 22, 2018

Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by the court’s four liberals, said cellphone location information “is detailed, encyclopedic and effortlessly compiled.” Roberts wrote that “an individual maintains a legitimate expectation of privacy in the record of his physical movements” as they are captured by cellphone towers.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://movietvtechgeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/supreme-court-ruling-on-cellphone-privacy-search-warrants-2018.pdf” title=”supreme court ruling on cellphone privacy search warrants 2018″]

Roberts said the court’s decision is limited to cellphone tracking information and does not affect other business records, including those held by banks. He also wrote that police still can respond to an emergency and obtain records without a warrant.

But the dissenting conservative justices, Anthony Kennedy, Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, cast doubt on Roberts’ claim that the decision was limited. Each wrote a dissenting opinion, and Kennedy said in his that the court’s “new and uncharted course will inhibit law enforcement” and “keep defendants and judges guessing for years to come.”

Roberts does not often line up with his liberal colleagues against a unified front of conservative justices, but digital-age privacy cases can cross ideological lines, as when the court unanimously said in 2014 that a warrant is needed before police can search the cellphone of someone they’ve just arrested.

The court ruled Friday in the case of Timothy Carpenter, who was sentenced to 116 years in prison for his role in a string of robberies of Radio Shack and T-Mobile stores in Michigan and Ohio. Cell tower records spanning 127 days, which investigators got without a warrant, bolstered the case against Carpenter.

Investigators obtained the records with a court order that requires a lower standard than the “probable cause” needed for a warrant. “Probable cause” requires strong evidence that a person has committed a crime.

The judge at Carpenter’s trial refused to suppress the records, finding no warrant was needed, and a federal appeals court agreed. The Trump administration said the lower court decisions should be upheld.

The American Civil Liberties Union, representing Carpenter, said a warrant would provide protection against unjustified government snooping.

“This is a groundbreaking victory for Americans’ privacy rights in the digital age. The Supreme Court has given privacy law an update that it has badly needed for many years, finally bringing it in line with the realities of modern life,” said ACLU attorney Nathan Freed Wessler, who argued the Supreme Court case in November.

The administration relied in part on a 1979 Supreme Court decision that treated phone records differently than the conversation in a phone call, for which a warrant generally is required.

The earlier case involved a single home telephone and the court said then that people had no expectation of privacy in the records of calls made and kept by the phone company.

“The government’s position fails to contend with the seismic shifts in digital technology that made possible the tracking of not only Carpenter’s location but also everyone else’s, not for a short period but for years and years,” Roberts wrote.

The court decided the 1979 case before the digital age, and even the law on which prosecutors relied to obtain an order for Carpenter’s records dates from 1986, when few people had cellphones.

The Supreme Court in recent years has acknowledged technology’s effects on privacy. In 2014, Roberts also wrote the opinion that police must generally get a warrant to search the cellphones of people they arrest. Other items people carry with them may be looked at without a warrant, after an arrest.

Roberts said then that a cellphone is almost “a feature of human anatomy.” On Friday, he returned to the metaphor to note that a phone “faithfully follows its owner beyond public thoroughfares and into private residences, doctor’s offices, political headquarters, and other potentially revealing locales.”

As a result, he said, “when the government tracks the location of a cell phone it achieves near perfect surveillance, as if it had attached an ankle monitor to the phone’s user.”

Even with the court’s ruling in Carpenter’s favor, it’s too soon to know whether he will benefit from Friday’s decision, said Harold Gurewitz, Carpenter’s lawyer in Detroit. The Cincinnati-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals will have to evaluate whether the cellphone tracking records can still be used against Carpenter under the “good faith” exception for law enforcement — evidence should not necessarily be thrown out if authorities obtained it in a way they thought the law required. There also is other evidence implicating Carpenter that might be sufficient to sustain his conviction.

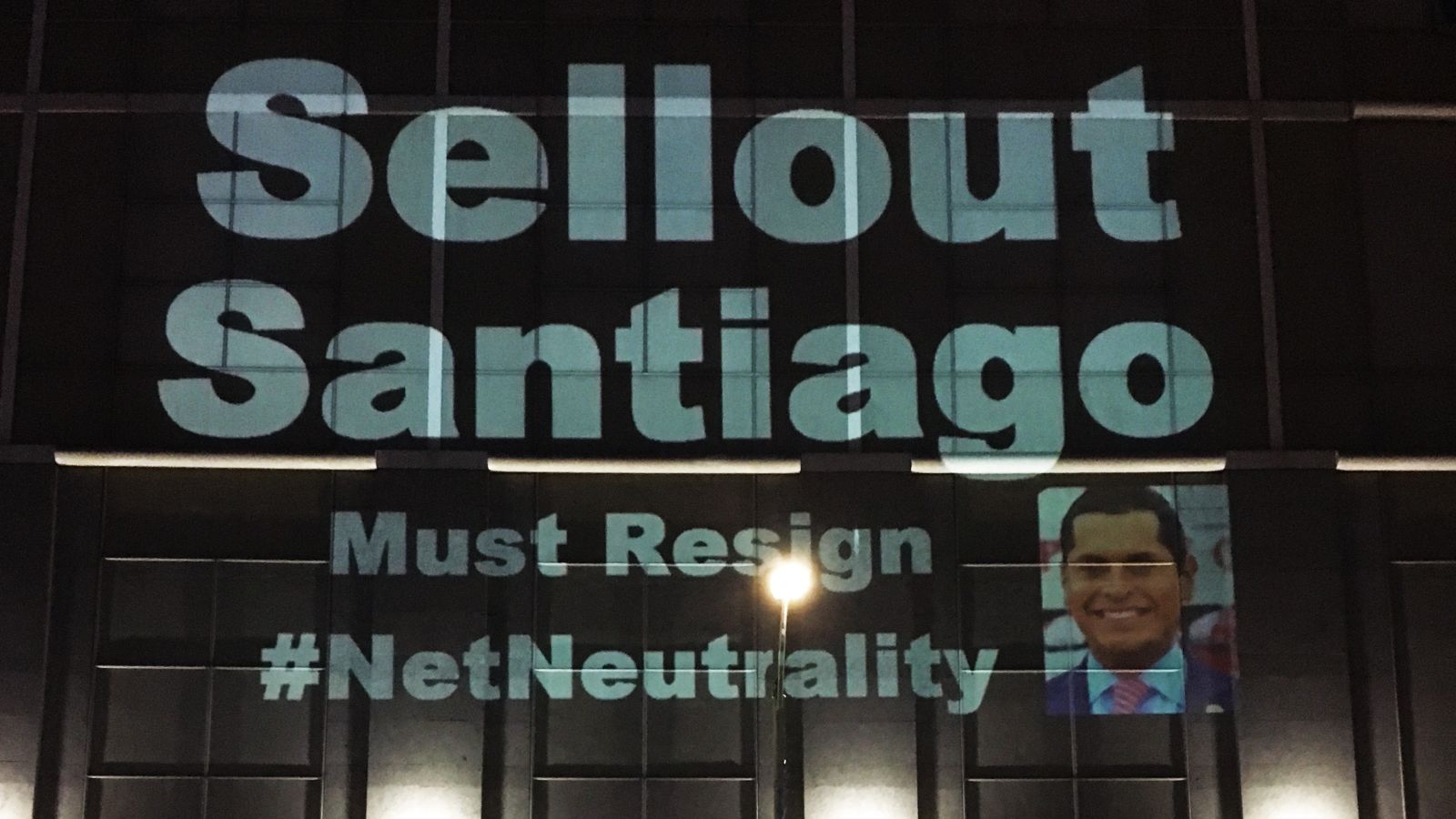

A California lawmaker’s decision to alter a net neutrality bill considered one of the nation’s most aggressive efforts to require an equal playing field on the internet has generated intensely personal online attacks aimed at his family as well as criticism from fellow Democrats in Congress.

Assemblyman Miguel Santiago leads a committee that this week stripped whole chunks of a net neutrality measure. He stirred a passionate reaction from open internet advocates who think the state that is home to the technology sector and the liberal resistance to President Donald Trump should take a hardline stance on the matter.

The decision reverberated far beyond California’s Capitol, drawing rebukes from members of Congress and leading the state Democratic chairman to try to diffuse tension. Santiago quickly drew fire in online memes and a flood of calls to his office accusing the Los Angeles lawmaker of selling out to internet providers, citing his contributions from AT&T.

“My personal family pictures have been stolen from my social media platforms and used to create memes,” Santiago wrote in a lengthy statement defending his move Friday. “This is a new low.”

One meme shows a picture of him with his wife and two children with text portraying a hypothetical conversation in which Santiago tells them how to be “a sellout whore” who is “just like daddy.” Facebook commenters urged people not to donate to the foundation where his wife works.

In his most thorough explanation for the decision to date, Santiago said he changed the bill to help it withstand legal muster. But the bill’s author, Democratic Sen. Scott Wiener of San Francisco, declared his measure “eviscerated” and “mutilated,” saying he couldn’t stand behind legislation that he doesn’t believe has teeth.

Wiener said the attacks on Santiago are inappropriate.

“That is fair game to criticize any elected official for the positions that we take,” Wiener said. “It’s not OK to attack people’s families or to engage in personal attacks.”

The Federal Communications Commission last year repealed Obama-era regulations that prevented internet companies from speeding up or slowing down the delivery of certain content.

The debate in California is being closely watched by net neutrality advocates around the country, who are looking to the state to pass sweeping net neutrality provisions that could drive momentum in other states, Marc Martin said, chair of the communications group at the law firm Perkins Coie.

“California’s got this very significant Democratic majority. If it can’t make it there, how’s it going to make it anywhere else?” Martin said.

Three states have adopted legislation that takes various approaches preserving net neutrality, but Wiener’s California bill was seen as the most comprehensive effort.

Wiener and Santiago both said they’re committed to improving the bill, though it’s unclear if their differences can be bridged.

Santiago has taken the bulk of the fire for amendments that were approved by eight of the 11 members of the Assembly Communications and Conveyance Committee.

The showdown represents the latest flashpoint in the Democratic Party over ideological purity. California Democratic Party chairman Eric Bauman attempted to defuse tension Thursday with a statement urging Santiago and Weiner to work together to find the right solution. He did not condemn Santiago’s actions.

The decision disappointed House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, her spokeswoman, Taylor Griffin, said in an email.

“It is our hope that the state legislature will find a solution to safeguard Californians from the Trump FCC’s misguided net neutrality decision and secure California’s rightful place as a national leader in the fight for an open internet for all,” Griffin said. Pelosi lives in San Francisco but rarely weights into state legislative issues.

Rep. Edward Markey of Massachusetts, who is leading a federal effort to revive net neutrality, was similarly critical, as were Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and actress Alyssa Milano.