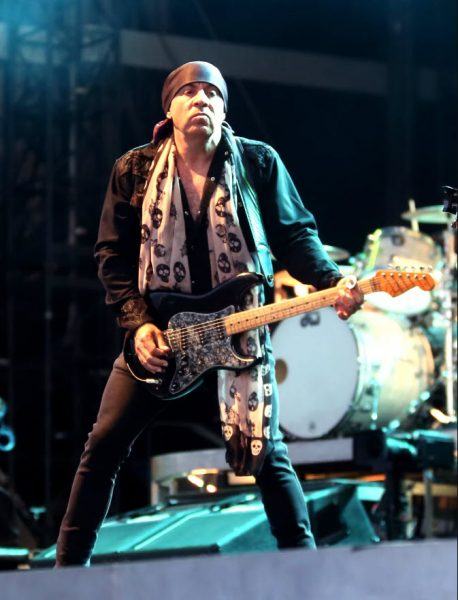

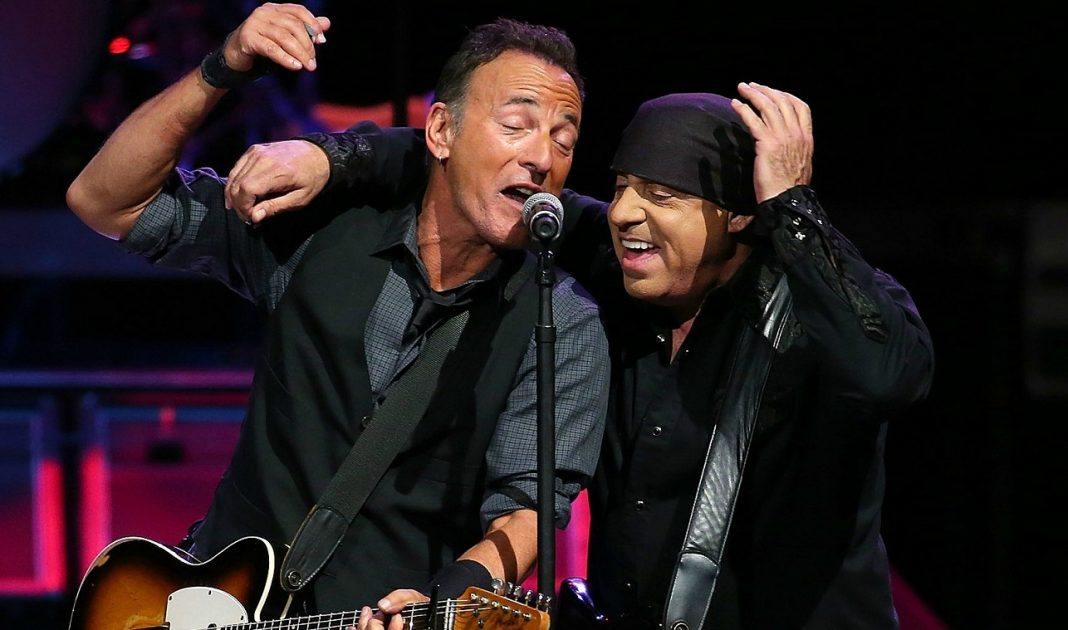

Steven Van Zandt has lived every wannabe rockers dream life being part of Bruce Springsteen’s “E Street Band” (not to mention his good friend) to playing a big role in a huge HBO hit “The Sopranos.” That would surpass most people’s wildest dreams, but Van Zandt has more to do.

Fans of his will know about his 80’s band Little Steven & The Disciples of Soul, so they’ll be excited about his new album that dropped earlier in May, “Summer of Sorcery.” He’s still politically active, and it doesn’t take much to get him talking. He’s not that celebrity that just does the PC talking points. He goes there, and if you love a great debate, this is your man.

There’s plenty of rock on Steven Van Zandt’s first album of original material in 20 years. There’s also soul and funk and some mean horn solos. What there isn’t plenty of is politics.

The bandana-wearing guitarist for Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, who in the past has never been shy about calling out politicians, has put aside partisanship in these divisive times.

“I’m trying to stay as nonpartisan as I can and provide some common ground,” he said. “When you’re as political as I was — and I was as political as it gets — for the hardcore fans of mine it’s going to take a bit of adjustment.”

Van Zandt, who in the past has raised his voice against apartheid and nuclear weapons, refuses to add kindling to what he considers a country “heading towards a civil war.” He wants his concerts to be a safe zone.

“Democrats, Republicans and independents are welcome to come to the show and enjoy themselves because it’s a strictly musical trip,” he said. “We need a break every now and then, in other words, and right now we’re providing that break.”

Van Zandt’s relief comes in the form of a new album, “Summer of Sorcery.” The 12-track collection sees him reteam with his 15-piece band, the Disciples of Soul, and mine what he calls a “rock-meets-soul thing.”

“It’s the first time in my life I’ve ever done two records in a row that were with the same band, first of all, and with the same sound — in the same genre, even. I’m going to stick with that now,” he said.

The album is a stew of Van Zandt’s influences, ranging from mambo to classic rock to doo-wop. There’s a flute solo in one song, and another name-checks Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys.

“There’s not a whole lot that’s good about getting older but there is one thing, which is you really tend to integrate your influences,” he said. “I like to have my influences on my sleeve. I do that intentionally, leaving little breadcrumbs for people to follow backwards, hoping that they do listen to the original artists.”

In addition to avoiding politics, the album is also not autobiographical, a first for the musician. For each song, Van Zandt wrote from a different character’s perspective. In “Superfly Terraplane,” he’s a millennial; in “Love Again,” he’s a world-weary traveler searching for love.

“I like the idea of just making the 12 little movies and play a different role in each one,” he said. “I analyzed myself to death in the ’80s and I was sick of me. So I was ready for exploring my imagination for a change.”

The idea of writing an entire album of new material came during the tour of Van Zandt’s 2017 album “Soulfire,” which was composed of covers and songs he had written for other artists but never cut himself.

“The brain cells that work towards writing your own records started to wake up,” he said. “The tour just started feeding in those ideas and basically we took the tour and put it in a blender and out popped these songs — basically exactly how I was hoping it would work and it did.”

Bruce Resnikoff, president/CEO at Universal Music Enterprises, calls Van Zandt “maybe the smartest musicologist you’ll ever meet.” He said Van Zandt effectively took 20 years off from his solo work to work with Springsteen, and returned to his sound as soon as he re-engaged with his own work.

“It’s almost as if he picked off where he left off,” Resnikoff said. “When he goes onstage with his own band, you get everything you saw of him in the E Street Band plus you get everything you remember of him as a solo artist. He’s phenomenal.”

Van Zandt is juggling plenty of projects, including a tour to support the new album. He’s just released the box set “Soulfire Live!,” which includes guest appearances from the likes of Springsteen and Paul McCartney. A two-volume set of his music for the “Lilyhammer” Netflix series comes out in July. A catalog box — including his five solo albums from the 1980s, the protest album “Sun City,” and live songs and extras — is due in the fall. He also confirmed that Springsteen has written an album for the E Street Band.

Then there’s ensuring that there’s a pipeline of music fans for the future. Van Zandt believes his “Underground Garage” radio show on Sirius XM has introduced about 1,000 new bands to the public in the past 17 years. And he recently founded the TeachRock project, which helps young people connect the history of popular music to classroom work across disciplines.

It has 150 free lesson plans online and 25,000 teachers have registered. Jackson Browne, Martin Scorsese, Bono and Springsteen have helped develop it.

Van Zandt was inspired to launch the initiative to “keep the arts in the DNA of the education system.” It works by connecting music to history and social studies. If a student loves Beyonce, they’ll soon learn about people who paved the way for her, like Aretha Franklin, and lessons about the gospel church, Detroit and the civil rights movement.

“Art is an absolutely necessary part of the quality of life and it also helps kids learn. It gives them a comfortable place to learn from,” he said.

Some of the reason Van Zandt has been less outspoken with his politics is to avoid having the curriculum accused of being partisan. “I wanted it to be a purely educational enterprise.”

His music, though, remains welcome to all.

“You will leave stronger than you came and leave happier than you came,” he says, “and maybe even be able to deal with this madness of the real world a little bit better.”

Your new documentary Asbury

Park: Riot, Redemption, Rock n Roll hasyou going back to an underage venue

called the Upstage Club where you spent a lot of your early summers. How

important was it to have that space as a young musician?

Van Zandt: It

was a miracle. Bruce discovered the Upstage Club and told me about it. He said:

‘You’ve got to come down, it’s crazy! It’s open ‘til 5AM.’ Everybody would go

there to jam. Jamming was the thing. That’s why I don’t jam to this day. I

jammed eight hours a night every night back then. Give me a two-and-a-half

minute song, please.

So you already knew Bruce Springstein

by that point?

Yeah, we’ve been

friends since ‘65. I had a band, he had a band. If you had a band in those

days, you were friends.

Was it already obvious when you were

teenagers that he was going to become Bruce Springsteen as we know him today?

Umm, no. He was

extremely quiet. Very grunge-like. He had long hair and he just looked down at

his feet when he played. There was no entertainment value. We hung out a lot

and then at a certain point I just felt he had something special about him. We

were the only freaks, misfits and outcasts who were left standing, saying: ‘We

don’t fit in anywhere. We better cling to this rock’n’roll thing, I don’t care

how big a longshot it is.’ And it was a longshot. It was important to me to have

at least one other person who felt like me.

He once said that your work

on “Born to Run” was “arguablySteve’s greatest contribution to my music”. Is it true you wrote

that guitar part?

No! I wish! It’s a long story, but basically… I fixed it. His career was in

danger. He had to save it with this one song, so he put everything into it.

They worked on it for months; the mix alone was weeks. So after all that he

calls me and says: ‘You’ve got to come up and hear my new song.’ He plays it.

I’m like: ‘That’s great! I really love that minor key riff! It’s so Roy

Orbison, or like something the Beatles would have done.’ He looks at me like:

‘What minor riff?’ I go: ‘You know, the minor chord in the riff!’ He goes:

‘There’s no fucking minor chord in the riff, what are you talking about?’

What it was is that he was bending a note, like a Duane Eddy thing, with a lot of reverb. You could hear where he was bending from but you couldn’t hear where he was bending to. They’d probably added more reverb as they went, and by the time they did the final mix you couldn’t hear it. Finally, he hears it! He was like: ‘Oh my fucking God!’ He broke the news to the powers that be. Oh, did they hate me. They had to redo it. He credits me with saving his career, which I probably did – more than once, by the way! It was really just a matter of fixing something. It changed the emotion of it. It was still great before, but it wasn’t quite as uplifting.

Recently, I saw someone play your

song “I Am a Patriot” [from 1984’s Voice

of America] at an environmental campaign event, and it got a really mixed

reaction. I think a lot of people the word ‘patriot’ meant it must be a song

for Donald Trump supporters.

That’s the whole

point. That same crowd thought “Born in the USA” was a Ronald Reagan campaign

song. That song is about the difference between patriotism and nationalism. It was

important to write it because I was being very critical of the government for

many years, and I wanted to make it clear I was being critical from a patriotic

point of view, in the true sense of the word, which is making sure the country

sticks to its ideals. The country’s ideals come before the political party.

We’ve forgotten that completely. It’s not about whose football team fucking

wins. That system has been a mess here, and it’s a disaster with Brexit.

If you had your way, what would your

solution be to Brexit?

I actually have a

solution. First of all, they should bring in a third, objective party to

arbitrate this, which no-one wants to do. If it was me, I’d spend two days with

the Leave people and hear all their complaints. I’d spend two days with the EU

and find out what’s going on there. Then I would have a solution within a week.

I’m not kidding. Now, whether they would execute this solution is another

matter. I was particularly pissed off that none of the Leave people gave a fuck

about Ireland. ‘Fuck Ireland, fuck Scotland, fuck everybody.’ I’m looking at

this going: ‘You really think you’re getting the British Empire back you

fucking assholes?’ What’s next, are you going to annex India?

Did you really originally audition

for the part of Tony Soprano?

Yeah, and I got it.

Did you land it? What led to James

Gandolfini getting the part?

HBO said to David

Chase: ‘Are you out of your fucking mind? We’re making the biggest investment

of our lives.’ People don’t remember, HBO was a very small channel with a

football show on. They were nothing. This was $30 million, which is probably

half an episode of Game of Thrones now but at the time was a

big seasonal commitment. He’s picking a guy who’s never acted before!

He came to me and said: ‘They won’t let me cast you. What else do you want to do?’ I said: ‘Now that I think about it, I’m feeling kind of guilty taking an actor’s job. They work their whole lives for this. I’m just a guitar player off the street.’ He said: ‘I tell you what, I’ll write a new part specifically for you so you’re not taking anyone else’s job.’ I had a treatment for a script that I’d been working on about an independent hitman named Silvio Dante who is semi-retired and has a club similar to the old Copacabana. It’s set in the present day but he kind of lives in the past. He’s a traditionalist, so it’s big bands, chorus girls, Jewish Catskills comics, the whole thing. Chase went away and thought about it and when he came back he said: ‘We can’t afford it. How about a strip club? You’ll run the strip club for the family.’ So that’s how the Bada Bing was born.

Do you think that Silvio and Tony’s

relationship is similar to yours and Bruce’s?

Yeah, I used that.

We decided that he’s gonna be the consigliere, chief advisor and best friend so

I wrote a whole story about them growing up together. My character was the only

one on the show who didn’t want to be the boss. He’s very happy being behind the

scenes. I knew very well what that dynamic is like, being the only guy not

afraid of the boss. You gotta be the one to bring the bad news occasionally,

and get the ire or the anger directed at you. I was quite used to that

position, so I used that. It worked out quite well actually. It’s amazing. I

miss Jimmy [Gandolfini] every day, we were so close. He was such a life force.

It’s still hard to believe.

This is one of those must-know questions. When you married your wife Maureen [who’d later play onscreen Sopranos wife Gabriella Dante] in 1982, you had Little Richard presiding over it. What’s a wedding like when the priest is Little Richard?

I can describe it in one word: chaos. Two words: blissful chaos. Of course, he lied and said he’d done it before. We picked a short sermon for him and he just went on and on. He’d become a preacher in ‘59, but it was one of those evangelical things… so I’m probably not legitimately married. Which, you know, [stage whisper:] I don’t want to say was part of the plan. But yeah, it was real rock’n’roll. Percy Sledge sang “When a Man Loves a Woman” when we walked down the aisle. We had Little Milton playing in one room, the band from The Godfather in another room. It was quite a scene.