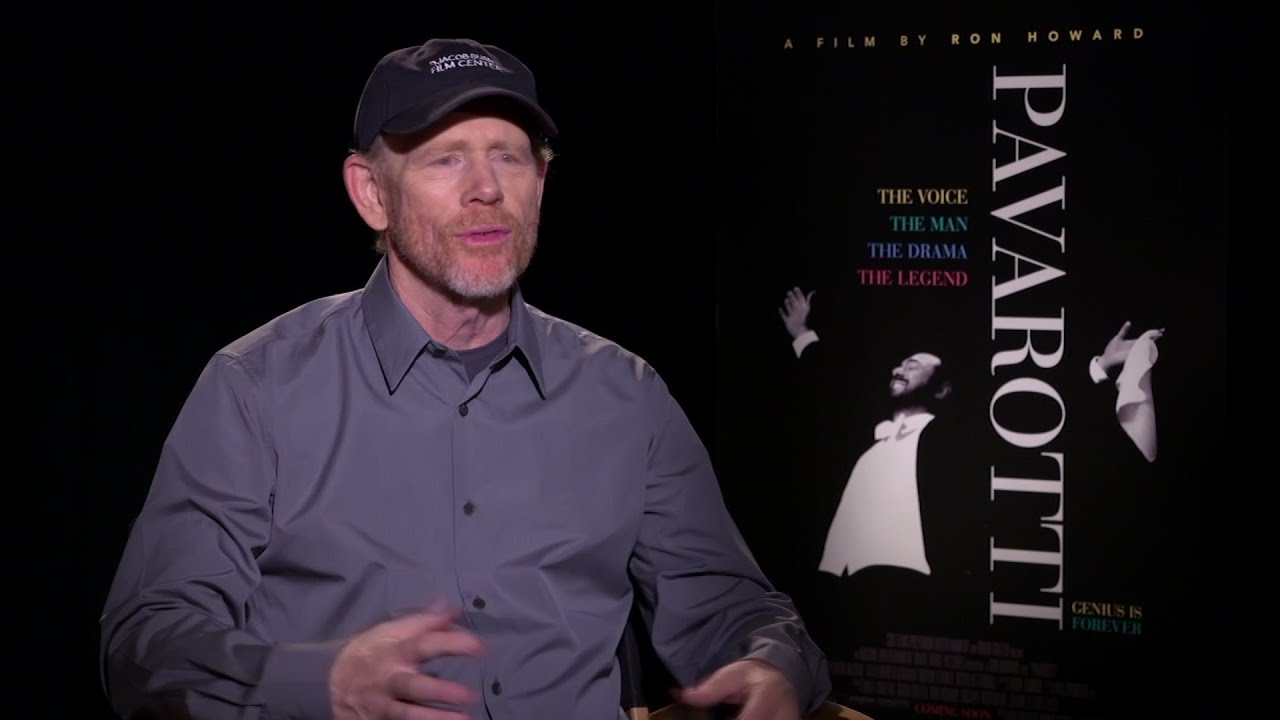

Most Ron Howard fans will be surprised to see him adding documentarian to his massive list of films, but no one seems more surprised than the man himself. He said that it was a format he’d always been interested in trying, but something about it intimidated him. Yes, even A-list directors get nervous. Documentaries might look easy, but they are far from that.

It was a series of fortuitous events beginning with advice from director Jonathan Demme and then getting an offer to direct a documentary about Jay-Z’s Made in America music festival. What better way to get your feet wet than covering a festival. He might have been nervous, but it didn’t stop Howard from jumping in feet first and now he’s on his third documentary.

As any documentarian will tell you, once you get the bug, you can’t stop. There’s something about the process of seeing things unfold in front of your eyes without a script. Then letting an audience share that same experience with you. Howard is no longer nervous and will continue making documentaries along with his scripted shows and films. With documentary films, it’s all about the subject matter that will get your passions burning, and Pavarotti seemed to do just that.

Ron Howard doesn’t remember meeting Luciano Pavarotti so much as feeling his presence. “My memory has less to do with my brief handshake and fleeting eye contact with the maestro and more to do with the fact that it was at this giant Golden Globes event with major movie stars and elite television stars,” the film director says. “But even with those people there, when he arrived, he was it. And that was in the early Eighties, before the Three Tenors even. He was beginning to have that kind of impact, at least on the creative community. The fact he was there meant more to all of us than anything.”

Howard even recalls seeing his first opera when he was 4 years old. Just don’t ask him to tell you much about it.

The budding child star and future director was in Austria with his parents to shoot a movie, and they took him to a performance at the Vienna State Opera House.

“I remember this soprano hitting this note in this unbelievable gown,” Howard said, gesturing with his arms to conjure up the scene, “There’s the set, she’s over here on the left in profile, and she’s singing, and she turns back to the actors and everybody’s going crazy, there’s a big ovation. I don’t know what opera it was.”

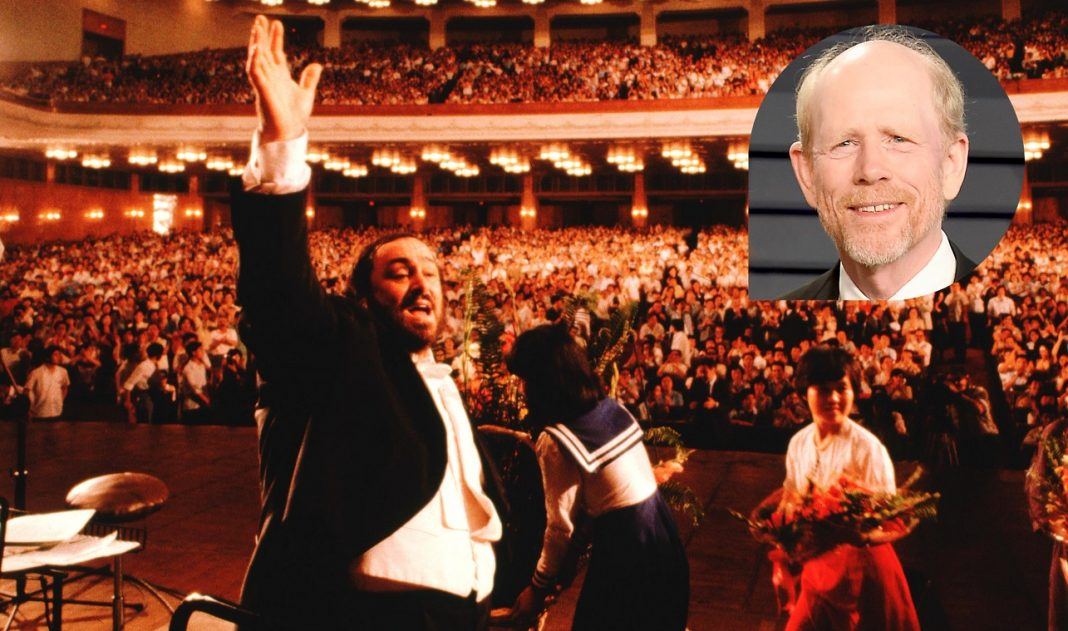

Not exactly the start of a lifelong love affair with opera. But in a way that makes Howard the perfect director for the new documentary “Pavarotti,” which is being released in the United States on Friday. Part biography and part greatest-hits concert, it aims to introduce Luciano Pavarotti to a new generation as well as to engage those who are already fans.

The Italian lyric tenor, who was born in Modena in 1935 and died of pancreatic cancer in 2007, was considered by many to have the most beautiful voice of his type since Enrico Caruso. He sang at leading opera houses for 40 years, sold millions of records as the “king of the high C’s,” and, with his endearing personality and love of publicity. became a household name in a way no opera star has since.

“We felt like it was a surprising story,” Howard says, including himself with the rest of the doc’s creative team, who helped him make “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week.” “Even though he’s a household name, there was so much that none of us really knew about his life, which turned out to be pretty operatic in its own right. The more I dug into the reading and watching performances, I, as a movie director, felt like the close-ups of him singing were akin to Brando in “A Streetcar Named Desire” or something. He’s so powerful, emotional and expressive.”

“Pavarotti” traces the opera legend’s life from his youth in war-torn Modena, Italy to the world stage through commentary from both of his wives, the daughters from his first marriage, the two surviving Three Tenors, Bono and many others, along with vintage interviews with the late singer. It contains rare footage and recordings, including shots of him performing in a choir with his father before his fame, a clip of him singing in “La Bohème” mere months after his stage debut and handkerchief-clutching performances in locales as varied as Liberty, Missouri, Brazil and Russia. There is also private home video footage he made for his family. Although it skates past a few rough patches in Pavarotti’s life, it provides insight into the singer’s desire to bring opera to everyone and just how he saw the world, prior to his death in 2007.

“I’d never seen him live, but I was well aware of his stature,” Howard said in a recent interview. “My hope is the film goes a step toward that agenda of his which was to democratize the art form and broaden the audience reach.”

Howard, known for his eclectic range from comedies like “Cocoon” and “Splash” to serious dramas like “Apollo 13” and “A Beautiful Mind” (which won him a directing Oscar), said he got involved in the project through producer Nigel Sinclair, with whom he had worked on a documentary called “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week.”

Researching the project, Howard studied the plots of Pavarotti’s signature operas like Puccini’s “La Boheme” and Donizetti’s “L’Elisir d’Amore” and the lyrics to his arias. That gave him an idea about how to structure his film.

“I thought, well, we might be able to use these arias to almost do an opera about Pavarotti that might give us an interesting framework,” he said. “To use the music to share with people his life’s journey.”

And quite a journey it was — from childhood poverty in wartime Italy to a rise to fame and riches; from marriage and three children to years of philandering and finally divorce and remarriage. Artistically, Pavarotti moved from performing mainly on opera stages to singing in large arenas before hundreds of thousands of people — including as part of the Three Tenors with Placido Domingo and Jose Carreras — and finally to collaborating with pop artists like Bono. And he was literally an outsize figure: With his love of food and Italian cooking, he constantly struggled with ballooning weight.

As he got more into it, Howard realized that people may know Pavarotti’s name but even opera buffs might not know the whole of the wild-haired vocal virtuoso’s outsized story, so he worked on making it accessible — much in the same way Pavarotti wanted to make opera itself more accessible. But in the end, Howard says he had a greater goal: “To deepen people’s understanding of how emotional his singing can be.” It’s something he felt firsthand.

“It’s a bittersweet story,” Howard said. “He lived the dream, he became Caruso, his era’s great example of a global superstar as an opera singer. And then he clearly lost his way emotionally.

“I think he set the bar so high for himself I’m not sure he could ever live up to what his ambitions were, for all fronts — life, his art, his personal relationships,” he said.

But Howard sees his film as “ultimately far more celebration than anything else, despite the turbulence that his life knew and his loved ones knew.” He thinks the singer was able to “reinvent himself” when he took up philanthropic causes, starting with his friendship with Prince Diana and involvement in her work for the Red Cross.

His ex-wife, Adua, and their three grown daughters reconciled with Pavarotti before his death, and they are interviewed here. So too is his second wife, Nicoletta, who recorded never-before-seen home movies in which Pavarotti voices regrets for his failings as a husband and father. In all, the filmmakers used more than 50 interviews, both archival and new, and excerpts from more than 20 arias.

The film touches only lightly on the vocal decline of Pavarotti’s later years, which some critics blamed on his loss of interest in the disciplined life of an opera singer.

“He wasn’t quite what he used to be,” Howard said. “Some people who watched him on his farewell tour felt he was relying more on his reputation.”

Howard said working on the film has “definitely” made him more interested in opera, though his tastes in music remain as varied as his choice of movie subjects.

He said he grew up listening to James Taylor, Cat Stevens and Simon and Garfunkel, and that bluegrass was “ingrained in me” from his days as Opie on “The Andy Griffith Show.”

“Andy liked to play, and our makeup guy played the banjo,” he said. “But there’s nothing I get locked into. I’m always popping around. Sometimes I’ll get into a jag of listening to obscure pop music from different countries.”

Ron Howard Q&A

What was the biggest surprise about Pavarotti’s life

for you?

The sheer joy he had, and the sort of maverick side of his life, whether that

had to do with his personal romantic relationships or choosing to sing with pop

stars to help bring awareness to opera or to raise money for philanthropic

programs. These things caused him a lot of grief. Often, he knew he was going

to be criticized and yet he chose to go ahead and engage in whatever it was he

believed in, either on principle or commitment to a cause.

In the interview that he did later with his second wife— a year or so before he died — he talks about how it hurts to be criticized. And you then recognize he would still choose to make these controversial decisions, whether they were personal or professional. That’s a brand of courage that I think is useful and important to acknowledge.

How hard was it to get his first wife, Adua, and second wife,

Nicoletta, in the same film?

Well, it’s very significant in that it’s the first time that the families have

really cooperated with each other to a significant degree. And yes, it was

difficult. I don’t think I would’ve done the movie without their cooperation

and involvement because I didn’t want to just skip through his career and the

headlines. What’s interesting to me is that despite the heartache, his family

loves him, misses him and wants him to be well remembered.

Has that bitter dispute over Pavarotti’s estate and will after he

died continued or did things get settled out?

There’s a lot of tension. It was very hard to go back and talk about some of

these things and hard for them to go back and see the movie. Their

participation, to me, is kind of inspiring. It’s almost a lesson in understanding

and even forgiving. They’re not forgetting, but they’re really coming to terms

with it in a way that’s admirable. And they did some of that when he was alive,

which is so powerful and moving to me. They talk about how, on his deathbed,

all of them, including ex-lovers who were never married to him, arrived to

connect with him. His first wife, as upsetting as it might have been, tried to

cook for him one last time. These things were very unexpected for all of us.

Did Plácido Domingo or José Carreras talk about any lingering

rivalries with Pavarotti as his fame did eclipse theirs.

No, just as they said on camera, they maintained that it was mostly fun and

games. With the Three Tenors, there were some business squabbles and things

like that. But all that got ironed out and we didn’t feel it made sense or

needed to be in the film.

What I love about that sequence in our movie is that while everybody knows about the Three Tenors, not very many people know why or how the act came to be, that it just began as a way to help get Carreras back out onstage and prove that he could still perform at that level. And boy, does he.

A few negative aspects of Pavarotti’s life that seemed significant

weren’t heavily represented in the film. Like the time he was booed at La Scala

right at the peak of his fame. His final tour also had many cancelled dates. Did

you intend to not go so deep into those parts?

Well, we did mention that he went through a period where he was cancelling

tours. On the final tour, we didn’t feel like that was as significant as the

way people were responding to his performances. And Bono’s defense was so

powerful and passionate that we ultimately decided to focus on that aspect of

the final tour.

La Scala was in 1992 when he was at the peak of his fame and long before his death. It generated a lot of negative press. In documentaries you cover the good and the bad so thus my question on that.

Well, that was also in that little period around the time where we say he was kind of having a midlife malaise. One of the critics that we have speaking in the film talks about how he was a little bit out at sea. I think that was around the time. The Tenors had happened, but it’s right around the time where he seemed to have this awakening around philanthropic projects.

And so, you know, you’re right. We didn’t play up that moment. But it wasn’t taken out particularly tactically or strategically. It really was just us trying to cover as much ground as we could and not repeat ourselves.

How did you get your hands on that amazing rare footage?

The family was making a lot of that available. There’s some great footage from

the wings when he’s doing “La Fille du Régiment,” where he’s hitting the High Cs. There are, like, seven or

eight of them in a row. I don’t think that’s been seen before, at least widely.

And we took pains to do a spectacular job mixing the audio.

How was that experience? Audio is such an integral part of film,

but it can sometimes be tedious.

Chris Jenkins, who mixed Eight Days a Week, wanted to go back to Abbey Road to

mix this. He was almost being superstitious about it, because we had a good

experience on The Beatles. So, we’re mixing and suddenly he finds out that in the big hall, the

LSO is about to record the next day, so the mics are all set up in the room to

record the orchestra. He asks permission to go in and record tracks. He

stripped out some of the vocals on some of Luciano’s performances and we

recorded it so that we could make the whole thing feel a little bit more in the

way we’re accustomed to hearing symphonic recordings.

Zubin Mehta, who conducted the Three Tenors, mentioned that whenever Pavarotti hit a high C, it would cause your ears to vibrate. Did you get that same experience?

I felt that, too, the last time we mixed the Three Tenors. The hairs went up on the back of my neck on our final soundcheck. Certainly, that kind of visceral response from the audience is something we were shooting for.

“Pavarotti” will be in theaters on June 7th.