Democrats, Republicans, wary Americans, and media outlets are waiting breathlessly for the new Senate health bill to finally be revealed on Thursday.

Mitch McConnell has kept this under wraps leading to much speculation of what to expect, but below are areas that are known. Republican Senator Ron Johnson has already warned that if he’s not given sufficient time to review this bill after it’s unveiling, he’ll be voting ‘no.’

Many Americans are feeling the same way as they’ve flooded Senator’s phone lines on the Hill.

So here’s what you can expect to take a hit on this version of healthcare.

Senate Republicans would cut Medicaid, end penalties for people not buying insurance and erase a raft of tax increases as part of their long-awaited plan to scuttle President Barack Obama‘s health care law, congressional aides and lobbyists say.

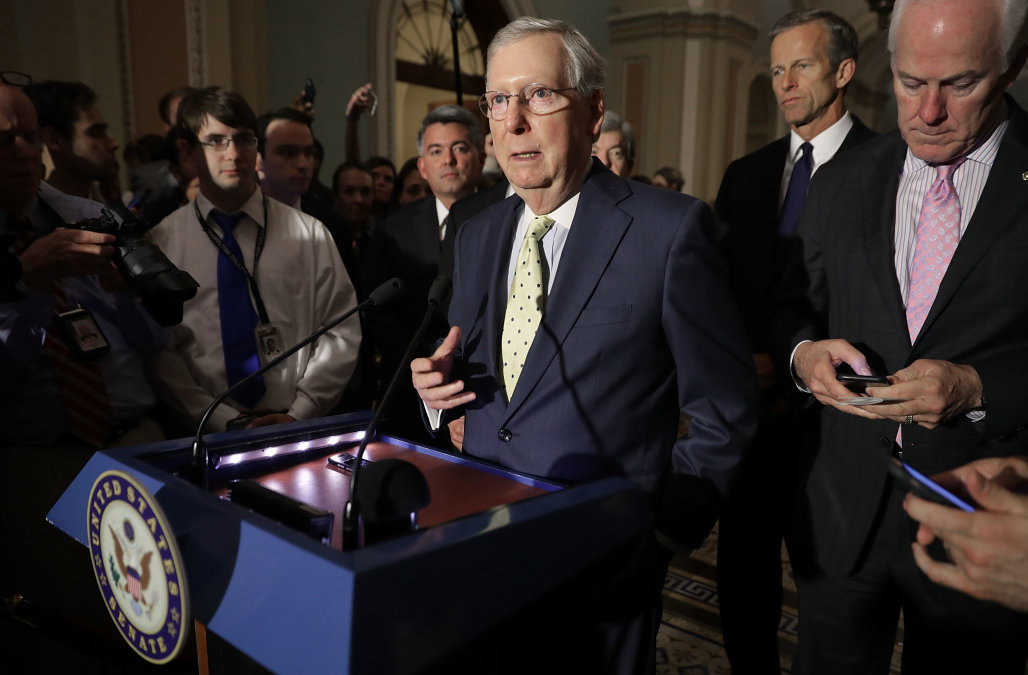

After weeks of closed-door meetings that angered Democrats and some Republicans, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell planned to release the proposal Thursday. The package represents McConnell’s attempt to quell criticism by party moderates and conservatives and win the support he needs in a vote he hopes to stage next week.

In a departure from the version the House approved last month, which President Donald Trump privately called “mean,” the Senate plan would drop the House’s waivers allowing states to let insurers boost premiums on some people with pre-existing conditions. It would also largely retain the subsidies Obama provided to help millions buy insurance, which are pegged mostly to people’s incomes and the premiums they pay.

The House’s tax credits were tied to people’s ages, a change the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said would boost out-of-pocket costs to many lower earners. Starting in 2020, the Senate version would begin shifting increasing amounts of tax credits away from higher earners, making more funds available to lower-income recipients, some officials said.

The emerging Senate bill was described by people on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss it publicly.

Facing uniform Democratic opposition, the Senate plan would fail if just three of the chamber’s 52 Republicans defect. More than half a dozen GOP senators have expressed problems with the measure, and a defeat would be a humiliating setback for Trump and McConnell on one of their party’s top priorities.

“We have a responsibility to move forward, and we are,” said McConnell, R-Ky.

GOP Senate leaders were eager for a seal of approval from Trump, who had urged them to produce a bill more “generous” than the House’s.

“They seem to be enthusiastic about what we’re producing tomorrow,” No. 2 Senate GOP leader John Cornyn of Texas said Wednesday of White House officials. “It’s going to be important to get the president’s support to get us across the finish line.”

Democrats say GOP characterizations of Obama’s law as failing are wrong, while the Republican effort would boot millions off coverage and leave others facing higher out-of-pocket costs. The budget office said the House bill would cause 23 million to lose coverage by 2026.

The sources said that, in some instances, the documents McConnell planned to release might suggest optional approaches for issues that remain in dispute among Republicans.

That could include the number of years the bill would take to phase out the extra money Obama provided to expand the federal-state Medicaid program for the poor and disabled to millions of additional low earners.

The House-passed bill would halt the extra funds for new beneficiaries in three years, a suggestion McConnell has offered. But Republicans from states that expanded Medicaid, like Ohio’s Rob Portman, want to extend that to seven years.

The Senate proposal would also impose annual limits on the federal Medicaid funds that would go to each state, which would tighten even further by the mid-2020s. Unlimited federal dollars now flow to each state for the program, covering all eligible beneficiaries and services.

The Senate would end the tax penalties Obama’s law created for people not buying insurance and larger employers not offering coverage to workers. The so-called individual mandate – aimed at keeping insurance markets solvent by prompting younger, healthier people to buy policies – has long been one of the GOP’s favorite targets.

To help pay for its expanded coverage to around 20 million more people, Obama’s law increased taxes on higher income people, medical industry companies and others, totaling around $1 trillion over a decade. Like the House bill, the Senate plan would repeal or delay many of those tax boosts.

The House waiver allowing higher premiums for some people with pre-existing serious illnesses was added shortly before that chamber approved its bill last month and helped attract conservative support. It has come under widespread criticism from Democrats and helped prompt some moderate House Republicans to vote against the measure.

Conservatives like Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., have warned they could oppose the bill if it doesn’t go far enough in dismantling Obama’s law. Moderates including Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, have expressed concern that the measure would cause many to lose coverage.