Netflix‘s exceptional “13 Reasons Why” show has come under fire for it’s graphic portrayal of suicide, and now a new study points a finger at it without being able to prove it. When I watched the graphic scene, I personally couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to do that as it wasn’t glamorous and looked extremely painful. I had my one teen son watch the show with me to understand the importance of communicating how he was feeling. I didn’t want to be the parent who missed all the signs and didn’t talk about this. It made a huge impact on him and wound up having him volunteer with a local suicide prevention hotline.

There are a multitude of reasons why people contemplate or commit suicide, and blaming it on one television show trying to make a difference isn’t the way to reach out to children going through this.

Suicides among U.S. kids aged 10 to 17 jumped by nearly a third to a 19-year high in the month following the release of a popular TV series that depicted a girl ending her life by cutting her wrists, researchers said.

The study published Monday can’t prove that the Netflix show “13 Reasons Why” was the cause, but there were 195 more youth suicides than would have been expected in the nine months following the show’s March 2017 release, given historical and seasonal suicide trends, the study estimated.

During April 2017 alone, 190 U.S. tweens and teens took their own lives. Their April 2017 suicide rate was .57 per 100,000 people, nearly 30 percent higher than in the preceding five years included in the study. An additional analysis found that the April rate was higher than in the previous 19 years, said lead author Jeff Bridge, a suicide researcher at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

“The creators of the series intentionally portrayed the suicide of the main character. It was a very graphic depiction of the suicide death,” which can trigger suicidal behavior, Bridge said.

Bridge acknowledged the study’s limitations included not knowing whether anyone who died by suicide had watched the show. Also, the researchers were not able to account for other factors that might have influenced suicides. Those include the April 19, 2017, suicide of former New England Patriots player Aaron Hernandez and a man accused of a Facebook-publicized killing who died by suicide the day before Hernandez. Bridge said those deaths couldn’t account for the spike the study found for the entire month of April.

“They nicely controlled for this by looking across years and showing a discontinuity for this particular year only,” said Matthew K. Nock, a psychologist at Harvard.

In the analysis, a team led by Jeffrey A. Bridge, of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, analyzed suicide data from the Center for Disease Control between January 2013 and December 2017. After correcting for trends and seasonal effects, the team found that rates did not exceed expected levels in 2017 for people over age 18.

The researchers analyzed data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on deaths in Americans aged 10 to 64 from January 2013 through December 2017. Their results were published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The researchers found no change in suicide rates in those 18 and older after the show was released.

The results are plausible and add to evidence that compelling media depictions of suicide can negatively influence young people, said sociologist Anna Mueller of the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the research.

“This is the first report I’ve seen like this, and of course it was our greatest fear that this might be a possibility” with the show, said Dr. Victor Schwartz, chief medical officer at the JED Foundation, a teen suicide prevention group.

Lisa Horowitz, a co-author and researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health, noted that suicide is the second leading cause of death for U.S. teens and called it “a major public health crisis.” Her agency helped pay for the study.

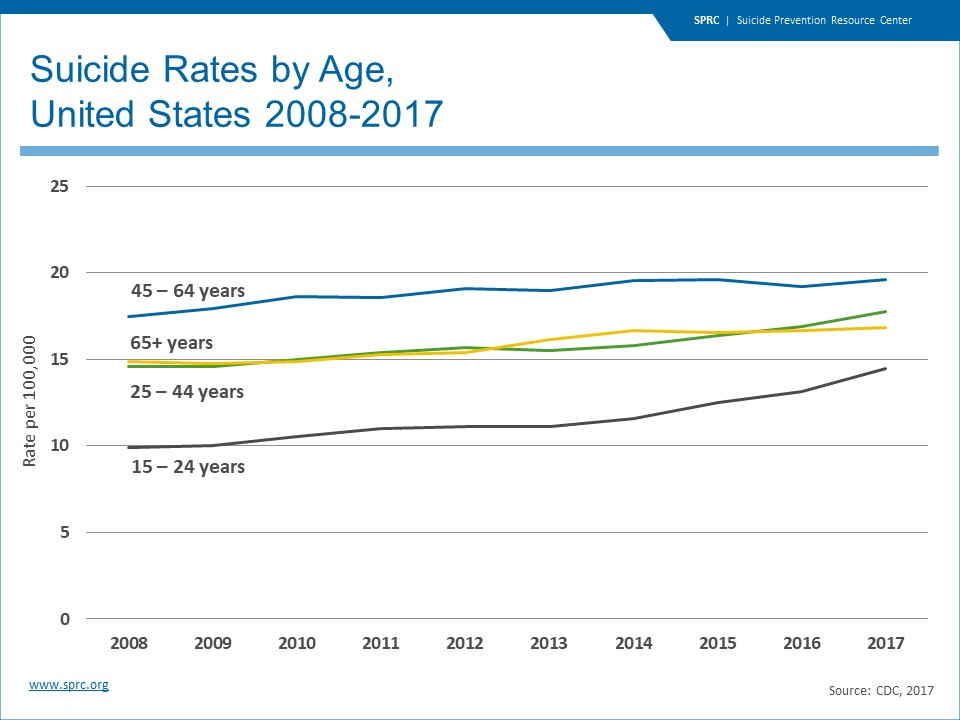

Teen suicide rates have increased in recent years and other research has suggested that bullying and heavy use of social media may contribute to the risk.

Netflix included warning messages with some of the episodes and created a website with crisis hotlines and other resources. In the second season, the show’s actors offered advice to viewers on where to seek help. The series’ third season will run later this year.

A Netflix spokesman noted that the new study conflicts with University of Pennsylvania research published last week that found fewer suicidal thoughts among young adults who watched the entire second season than among non-viewers.

“We’ve just seen the study and are looking into the research,” he said. “This is a critically important topic and we have worked hard to ensure that we handle this sensitive issue responsibly.”

Horowitz said the new results highlight how important it is for parents and other adults to connect with young people.

“Start a conversation, ask how are they coping with the ups and downs of life, and don’t be afraid to ask about suicide,” she said. It’s a myth that just asking might be a trigger, Horowitz said.

“One of the best ways to prevent is to ask,” she said.

Dr. Schwartz also said that Netflix had consulted with the JED Foundation along the way, and that the second season had incorporated several of his group’s recommendations.

In a surprise, boys accounted for almost all of the increase in 2017. The research team had anticipated that girls, identifying with the star of the show, would be more vulnerable. Dr. Horowitz said that looking at suicide-attempt data, which the researchers did not have, might have told another story.