Remember when Republicans said that they had to absolutely pass a healthcare plan before they could start on a tax reform one? They said that the former was needed to support the other.

Suddenly, that has been forgotten, and it’s full steam ahead to get a rather large tax reform plan in action by Christmas. Naturally, the majority of Republicans are praising this plan which gets rid of that pesky inheritance tax they keep saying they are doing for all the farmers out there. Growing up in a farming community, I knew of no farmers (even the large ones) that had any worry about that tax. It’s more for the ultra-wealthy like Donald Trump and his Goldman Sachs friends.

Donald Trump is touting that he’s giving Americans a big Christmas gift with this tax plan, but you need to look further to realize it’s not a gift for that 30% base of his. It will be more of a benefit to the 1% that those 30% folks aren’t so crazy about.

Good news is that it wasn’t called the Cuts, Cuts, Cuts Act as Trump originally wanted, but the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act which you can see in full below.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://movietvtechgeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/363309136-Republican-Tax-Bill.pdf” title=”Republican Tax Cuts and Job Act November 2017″]

With fanfare and a White House kickoff, House Republicans unfurled a broad tax-overhaul plan Thursday that would touch virtually all Americans and the economy’s every corner, mingling sharply lower rates for corporations and reduced personal taxes for many with fewer deductions for home-buyers and families with steep medical bills.

The measure, which would be the most extensive rewrite of the nation’s tax code in three decades, is the product of a party that faces increasing pressure to produce a marquee legislative victory of some sort before next year’s elections. GOP leaders touted the plan as a sparkplug for the economy and a boon to the middle class and christened it the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

“We are working to give the American people a giant tax cut for Christmas,” President Donald Trump said in the Oval Office. The measure, he said, “will also be tax reform, and it will create jobs.”

It would also increase the national debt, a problem for some Republicans. And Democrats attacked the proposal as the GOP’s latest bonanza for the rich, with a phase-out of the inheritance tax and repeal of the alternative minimum tax on the highest earners — certain to help Trump and members of his family and Cabinet, among others.

And there was enough discontent among Republicans and business groups to leave the legislation’s fate uncertain in a journey through Congress that leaders hope will deposit a landmark bill on Trump’s desk by year’s end.

Underscoring problems ahead, some Republicans from high-tax Northeastern states expressed opposition to the measure’s elimination of the deduction for state and local income taxes. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch of Utah called the House measure “a great starting point” but said it would be “somewhat miraculous” if its corporate tax rate reduction to 20 percent — a major Trump goal — survived. His panel plans to produce its own tax package in the coming days.

The House Republicans’ plan, which took them months to craft in countless closed-door meetings, represents the first step in their effort to reverse what’s been a politically disastrous year in Congress. Their drive to obliterate President Barack Obama’s health care law crashed, and GOP lawmakers concede that if the tax measure collapses, their congressional majorities are at risk in next November’s elections.

The package’s tax reductions would outweigh its loophole closers by a massive $1.5 trillion over the coming decade. Many Republicans were willing to add that to the nation’s soaring debt as a price for claiming a resounding tax victory. But it was likely to pose a problem for others — one of several brushfires leaders will need to extinguish to get the measure through Congress.

Republicans must keep their plan’s shortfall from spilling over that $1.5 trillion line or the measure will lose its protection against Democratic Senate filibusters, bill-killing delays that take 60 votes to overcome. There are just 52 GOP senators and unanimous Democratic opposition is likely.

The bill would telescope today’s seven personal income tax brackets into just four: 12 percent, 25 percent, 35 percent and 39.6 percent.

— The 25 percent rate would start at $45,000 for individuals and $90,000 for married couples.

— The 35 percent rate would apply to family income exceeding $260,000 and individual income over $200,000, which means many upper-income families whose top rate is currently 33 percent would face higher taxes.

— The top rate threshold, now $418,400 for individuals and $470,700 for couples, would rise to $500,000 and $1 million.

The standard deduction — used by people who don’t itemize, around two-thirds of taxpayers — would nearly double to $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for couples. That’s expected to encourage even more people to use the standard deduction with a simplified tax form Republicans say will be postcard-sized.

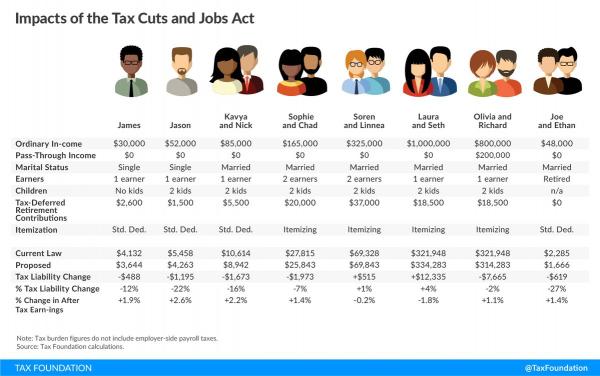

Many middle-income families would pay less, thanks to the bigger standard deduction and an increased child tax credit. Republicans said their plan would save $1,182 in taxes for a family of four earning $59,000, but features like phase-outs of some benefits suggest their taxes could grow in the future.

“The plan clearly chooses corporate CEOs and hedge fund managers over teachers and police officers,” said Rep. Bill Pascrell, D-N.J.

One trade-off for the plan’s reductions was its elimination of breaks that millions have long treasured. Gone would be deductions for people’s medical expenses — especially important for families facing nursing home bills or lacking insurance — and their ability to write off state and local income taxes. The mortgage interest deduction would be limited to the first $500,000 of the loan, down from the current $1 million ceiling.

Led by Rep. Kevin Brady, R-Texas, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, the authors retained the deductibility of up to $10,000 in local property taxes in a bid to line up votes from Republicans from the Northeast. The panel planned to begin votes on the proposal next Monday.

“It’s progress, but I want more,” said Rep. Leonard Lance, R-N.J., who represents one of his state’s wealthier, higher-cost districts and wants the entire property tax deduction restored.

On the business side, the House would drop the top rate for corporations from 35 percent to 20 percent. American companies operating abroad would pay a 10 percent tax on their overseas subsidiaries’ profits. Cash that those firms have amassed abroad but now return home would face a one-time 12 percent tax.

Also reduced to 25 percent would be the rate for many “pass-through” businesses, whose profits are taxed at the owners’ individual rate.

But some of those companies would face higher rates. Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., said that disparity was “just not acceptable,” and the National Federation of Independent Business said it opposed the bill because it “does not help most small businesses.”

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce praised the measure but said “a lot of work remains to be done.” The group’s chief policy officer, Neil Bradley, said pass-throughs were one concern.

So, who wins and who loses?

Winners

Big corporations. American mega-businesses would get a substantial tax reduction. The bill cuts the top rate that large corporations pay from 35 percent to 20 percent, the biggest one-time drop in the big-business tax rate ever. On top of that, companies would get some new tax breaks to help lower their bills, such as the ability to deduct all the costs of purchasing new equipment, as well as a special low rate on any money they bring back to the United States from low-tax countries such as Ireland. Many businesses have been holding cash overseas to avoid 35 percent U.S. taxes. Now they would get to bring the money home at a tax rate of 12 percent. The entire business tax system would also change from a worldwide system, in which money anywhere around the globe is taxed, to a territorial system in which it’s mostly money made in the United States that is taxed. Businesses have long lobbied for this change.

The super-rich. The estate tax often called the “death tax” by its critics, would go away by 2024, meaning wealthy families would be able to pass on lavish estates and trust funds to their heirs tax-free. At the moment, only estates worth over $5.49 million face the estate tax (the GOP plan doubles that amount immediately until the tax goes totally away). The mega-wealthy also would get to keep charitable deductions, a popular way to lower their tax bills, and they no longer would have to pay the alternative minimum tax (AMT), a safeguard against excessive tax dodging that’s been in place since 1969.

People paying the AMT. The bill eliminates the alternative minimum tax, which forces people who earn more than about $130,000 to calculate their taxes twice, once with all the deductions they can find and once with the AMT method, which prevents most tax breaks. There is perhaps no better example of how much this will benefit the rich than that fact that Donald Trump would have paid $31 million less in taxes in 2005 (the one year for which we have his tax returns) without the AMT.

“Pass through” companies. Some wealthy Americans who run businesses structured as sole proprietorships, partnerships or LLCs would get a sizable discount on their taxes. Under the GOP bill, these “pass through” companies would pay a tax rate of only 25 percent on 30 percent of their business income, a big reduction from the 39.6 percent rate some pay now. The bill tries to prevent “service firms” like law firms and accounting firms from being able to pay the lower 25 percent rate, but a good tax lawyer can probably make a case for these firms to qualify. Also, on the campaign trail, Trump said that hedge funds were “getting away with murder” on their taxes and that he would take away carried interest, the popular opening in the tax code these Wall Street titans use. But the bill does not change or eliminate carried interest, which is also used by some real estate developers.

Losers

Home builders. The legislation would cut in half the mortgage interest deduction used by millions of American homeowners, changing the deduction’s rules for new mortgages. Presently, Americans can deduct interest payments made on their first $1 million worth of home loans. Under the bill, for new mortgages, they would be able to deduct interest payments made only on their first $500,000 worth of home loans.

Home-builder stocks are plummeting as a result, since many builders make a lot of their money from constructing high-end mansions. In addition to capping the mortgage deduction, the bill also caps the state-and-local-property-tax deduction to $10,000 a year, another hit to higher-end homeowners. That said, many economists and even some Democrats say these limits are a good idea because the housing incentives in the current tax code favor the wealthy. The National Low Income Housing Coalition says mortgages over $500,000 are rare: Only 5 percent of mortgages are more than that amount.

(Some) small-business owners. The National Federation of Independent Business, which represents 325,000 small businesses, said it would not support the GOP bill, because it “leaves too many small businesses behind.” The original idea was to lower small businesses’ taxes to 25 percent, but the language in the bill allows small-business owners to pay only 30 percent of their business income at the 25 percent rate. The rest would be paid at the business owner’s individual tax rate. Any individuals earning over $200,000 a year (or couples earning more than $260,000) would pay the rest of their taxes at a rate of 35 percent.

People in high-tax blue states. Say goodbye to most of the state-and-local-tax deduction (SALT). Over a third of filers in many Democratic states such as California, New York, New Jersey and Connecticut claim the SALT deduction on their returns. Under the GOP plan, people would still be able to deduct up to $10,000 on the property taxes they pay locally, but they would no longer be able to deduct the other taxes they pay to state or local governments from their federal tax payments.

The working poor. While the bill includes lots of tax breaks for big businesses and the rich, the bottom 35 percent of Americans do not get any extra benefits, according to Lily Batchelder, who served on President Barack Obama’s National Economic Council. They already have a $0 federal tax liability. Some argue a more equitable tax system would increase the credits (money back) that lower-income families get, especially those that work low-wage jobs. The GOP preserves the earned-income tax credit, a popular refundable credit for the working class, but the bill does not expand it.

Charities. The National Council of Nonprofits warns that charitable deductions are likely to go down under this bill. While the GOP enables the wealthy to continue deducting their charitable giving, many middle- and upper-middle-class families would no longer get that tax break, because they probably would stop itemizing their deductions. At the moment about 30 percent of Americans itemize, but under the GOP bill, the standard deduction roughly doubles from $6,350 to $12,000 for individuals and $12,700 to $24,000 for married couples, meaning fewer people would probably itemize. The GOP argues that middle-class people should end up giving more to charity since they will pay less in taxes.