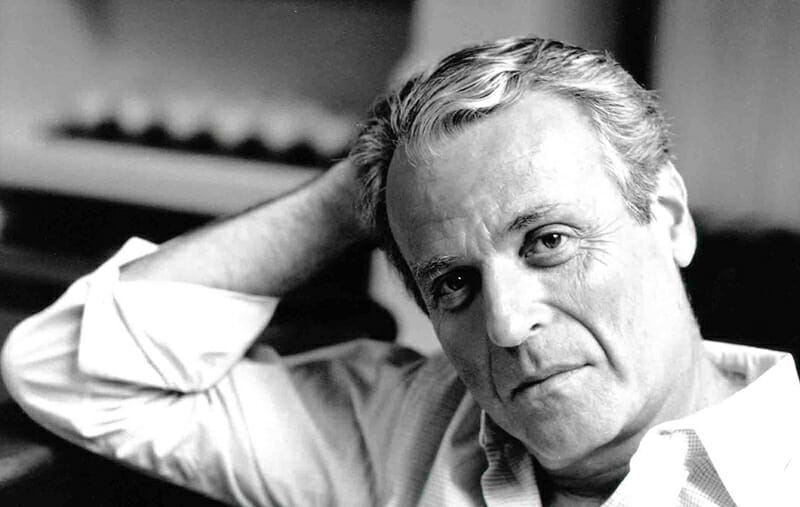

RIP William Goldman at 87: ‘Marathon Man,’ ‘All the President’s Men’ and ‘Good Will Hunting’ rumor

Click to read the full story: RIP William Goldman at 87: ‘Marathon Man,’ ‘All the President’s Men’ and ‘Good Will Hunting’ rumor

Known for writing the multi-Academy Award winning films “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and “All the President’s Men” among others, William Goldman hs died at the age of 87. He was also rumored to have written the bulk of Ben Affleck and Matt Damon’s “Good Will Hunting” which they won an Oscar for.

Goldman’s daughter, Jenny, said her father died early Friday in New York due to complications from colon cancer and pneumonia. “So much of what’s he’s written can express who he was and what he was about,” she said, adding that the last few weeks, while Goldman was ailing, revealed just how many people considered him family.

Goldman, who also converted his novels “Marathon Man,” ″Magic” and “The Princess Bride” into screenplays, clearly knew more than most about what the audience wanted, despite his famous and oft-repeated proclamation. He penned a litany of box-office hits, was an in-demand script doctor and carved some of the most indelible phrases in cinema history into the American consciousness.

Goldman made political history by coining the phrase “follow the money” in his script for “All the President’s Men,” adapted from the book by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein on the Watergate political scandal. The film starred Robert Redford as Woodward and Dustin Hoffman as Bernstein. Standing in the shadows, Hal Holbrook was the mystery man code-named Deep Throat who helped the reporters pursue the evidence. His advice, “Follow the money,” became so widely quoted that few people realized it was never said during the actual scandal.

A confirmed New Yorker, Goldman declined to work in Hollywood. Instead, he would fly to Los Angeles for two-day conferences with directors and producers, then return home to fashion a script, which he did with amazing speed. In his 1985 book, “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” he expressed disdain for an industry that elaborately produced and tested a movie, only to see it dismissed by the public during its first weekend in theaters.

“Nobody knows anything,” he wrote.

In the book, Goldman also summed up to the screenwriter’s low stature in Hollywood. “In terms of authority, screenwriters rank somewhere between the man who guards the studio gate and the man who runs the studio (this week),” wrote Goldman.

But for a generation of screenwriters, including Aaron Sorkin, Goldman was a mentor.

“He was the dean of American screenwriters and generations of filmmakers will continue to walk in the footprints he laid,” Sorkin said in a statement. “He wrote so many unforgettable movies, so many thunderous novels and works of non-fiction, and while I’ll always wish he’d written one more, I’ll always be grateful for what he’s left us.”

Goldman launched his writing career after receiving a master’s degree in English from Columbia University in 1956. Weary of academia, he declined the chance to earn a Ph.D., choosing instead to write the novel “The Temple of Gold” in 10 days. Knopf agreed to publish it.

“If the book had not been taken,” he told an interviewer, “I would have gone into advertising … or something.”

Instead, he wrote other novels, including “Soldier in the Rain,” which became a movie starring Steve McQueen. Goldman also co-authored a play and a musical with his older brother, James, but both failed on Broadway. (James Goldman would later write the historical play “The Lion in Winter,” which he converted to film, winning the 1968 Oscar for best adapted screenplay.)

William Goldman had come to screenwriting by accident after actor Cliff Robertson read one of his books, “No Way to Treat a Lady,” and thought it was a film treatment. After he hired the young writer to fashion a script from a short story, Goldman rushed out to buy a book on screen writing. Robertson rejected the script but found Goldman a job working on a screenplay for a British thriller. After that, he adapted his novel “Harper” for a 1966 film starring Paul Newman as a private eye.

He broke through in 1969 with the blockbuster “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” starring Newman and Redford. Based on the exploits of the real-life “Hole in the Wall” gang of bank robbers, the movie began a long association with Redford, who also appeared in “The Hot Rock,” ″The Great Waldo Pepper” and “Indecent Proposal.” Goldman’s script set a then-record $400,000 (or about $2.9 million today).

Though the sum made Goldman a target in an industry that had long devalued screenwriters, the price proved worth it. “Butch Cassidy” was the year’s biggest box office hit, grossing $102 million (or close to $700 million today).

“All the President’s Men” (1976) further enhanced Goldman’s reputation as a master screenwriter, though he initially had a low opinion of the project (“Politics were anathema at the box office, the material was talky, there was no action,” he later wrote) and was even regretful afterward because of the production’s headaches, including the use of multiple writers.

Other notable Goldman films included “The Stepford Wives,” ″A Bridge Too Far” and “Misery.” The latter, adapted from a Stephen King suspense novel, won the 1990 Oscar for Kathy Bates as lead actress.

In 1961 Goldman married Ilene Jones, a photographer, and they had two daughters, Jenny and Susanna. The couple divorced in 1991. Goldman passed away Friday in the Manhattan home of his partner, Susan Burden.

Born in Chicago on Aug. 12, 1931, Goldman grew up in the suburb of Highland Park. He graduated from Oberlin College in 1952 and served two years in the Army.

Goldman wrote more than 20 novels, some of them under pen names. “The Princess Bride,” published in 1973, was presented as Goldman’s abridgment of an older version by “S. Morgenstern.” The scheme, he said, was liberating.

“I never had a writing experience like it. I went back and wrote the chapter about Bill Goldman being at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and it all just came out. I never felt as strongly connected emotionally to any writing of mine in my life,” Goldman once said. “It was totally new and satisfying, and it came as such a contrast to the world I had been doing in the films that I wanted to be a novelist again.”

The film grew into a cult classic, adding more phrases of Goldman’s to the lexicon: “As you wish,” ″Inconceivable!” and “Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die!”

Despite all his success as a screenwriter, Goldman always considered himself a novelist and didn’t rate his scripts as great artistic achievements.

“A screenplay is a piece of carpentry,” he once said. “And except in the case of Ingmar Bergman, it’s not an art, it’s a craft.”

Goldman accidentally reignited the Hollywood insider rumors that he was actually the author of “Good Will Hunting,” and Miramax wanted to capitalize on marketing two cute young men for the Oscar win. He wrote this segment as tongue in cheek in his book “Which Lie Did I Tell?”

Doctoring is tricky, particularly when it comes to taking credit for success (or blame for failure). Of course, what I’m best known for of late is the the doctoring job I did on Good Will Hunting. If you go on the net and look up my credits, there it is, the previously uncredited work on that Oscar-winning smash.

The truth? I did not just doctor it. I wrote the whole thing from scratch. Though I had spent at most but a month of my life in Boston, and though I was 65 when the movie came out, I have been obsessed since my Chicago childhood with class as it exists in that great Massachusetts city. My basic problem was not the wonderful story or the genuine depth of the characters I created, it was that no one would believe I wrote it. It was such a departure for me.

What’s a mother to do? Here was my solution – I had met these two very untalented, very out-of-work performers, Affleck and Damon. They were both in need of money. The deal we struck was this: I would give them initial credit, they would front for me at the start, and then, once we were set up, the truth would come out.

You know what happened. Miramax got the flick, decided to use them in the leads, decided I would kill the commercial value of the flick if the truth were known. [Miramax boss] Harvey Weinstein gave me a lot of money for my silence, plus 20 percent of the gross.

Which is why I’m writing this from the Riviera.

I think the reason the world was so anxious to believe Matt Damon and Ben Affleck didn’t write their script was simple jealousy. They were young and cute and famous; kill the ****ers.

The real truth is that Castle Rock had the movie first, and Rob Reiner, no fool he, was given it for comments. Rob had one biggie.

Affleck and Damon in an early draft had a whole sub-plot about how the government was after Damon, the maths genius, to do subversive work for them. There were chases and action scenes, and what Rob told them was this: lose that aspect and stick with the characters.

When I read it, and spent a day with the writers, all I said was this: Rob’s dead right.

Period. Total contribution: zero.

But I’ll bet in some corner of your little dark hearts, you’re still saying bull****. I mean, it’s been five years and what else have they done? Nada.

Now I’ll tell you the real truth. Every word is mine. Not only that, I’m the guy who convinced James Cameron that the ship had to hit the iceberg…

Most people missed the final paragraph and insisted that Goldman has verified what they felt they already knew. He had a sense of humor which sometimes didn’t always come across, but he left a wonderful legacy of great films to watch over and over.

The post RIP William Goldman at 87: ‘Marathon Man,’ ‘All the President’s Men’ and ‘Good Will Hunting’ rumor appeared first on Movie TV Tech Geeks News By: George Cando