Marlon Brando was ‘The Godfather’ of Academy Award political speeches

Click to read the full story: Marlon Brando was ‘The Godfather’ of Academy Award political speeches

Political speeches at the Academy Awards might feel like a time honored tradition, but they’ve not been going on for as long as many would think. Plus, you can thank actor Marlon Brando for starting the tradition of political causes getting promoted over the standard ‘thank yous’ to the industry.

So, love them or hate them, Brando kicked it all off.

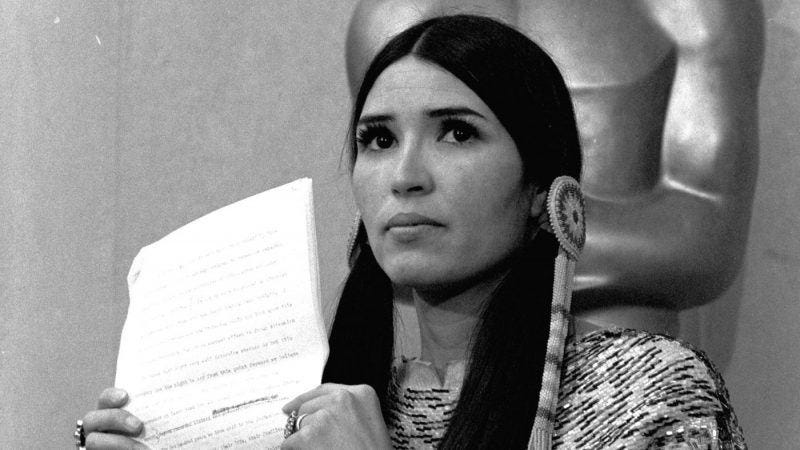

Brando’s role as Vito Corleone in “The Godfather” remains a signature performance in movie history. But his response to winning an Academy Award was truly groundbreaking. Upending a decades-long tradition of tears, nervous humor, thank-yous and general good will, he sent actress Sacheen Littlefeather in his place to the 1973 ceremony to protest Hollywood’s treatment of American Indians. In the years since, winners have brought up everything from climate change (Leonardo DiCaprio, “The Revenant,” 2016) to abortion (John Irving, screenplay winner in 2000) to equal pay for women, Patricia Arquette, best supporting actress winner in 2015 for “Boyhood.”

“Speeches for a long time were relatively quiet in part because of the control of the studio system,” says James Piazza, who with Gail Kinn wrote “The Academy Awards: The Complete History of Oscar,” published in 2002. “There had been some controversy, like when George C. Scott refused his Oscar for ‘Patton’ (which came out in 1970). But Brando’s speech really broke the mold.”

Producers for this year’s Oscars show have said they want to emphasize the movies themselves, but between the #MeToo movement and Hollywood’s general disdain for President Donald Trump, political or social statements appear likely at the March 4 ceremony. Winners at January’s Golden Globes citing the treatment of women included Laura Dern and Reese Witherspoon, who thanked “everyone who broke their silence this year.” Honorary Globe winner Oprah Winfrey, in a speech that had some encouraging her to run for president, noted that “women have not been heard or believed if they dare speak the truth to the power of those men. But their time is up. Their time is up. Their time is up.”

Before Brando, winners avoided making news even if the time was right and the audience never bigger. Gregory Peck, who won for best actor in 1963 as Atticus Finch in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” said nothing about the film’s racial theme even though he frequently spoke about it in interviews. When Sidney Poitier became the first black to win best actor, for “Lilies of the Field” in 1964, he spoke of the “long journey” that brought him to the stage, but otherwise made no comment on his milestone. When Jane Fonda, the most politicized of actresses, won for “Klute” in 1972, her speech was brief and uneventful.

“There’s a great deal to say, but I’m not going to say it tonight,” she stated. “I would just like to thank you very much.”

Political movements from anti-communism to civil rights were mostly ignored in their time. According to the movie academy’s database of Oscar speeches, the term “McCarthyism” was not used until 2014, when Harry Belafonte mentioned it upon receiving the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. “Vietnam” was not spoken until the ceremony held April 8, 1975, just weeks before North Vietnamese troops overran Saigon. No winner said the words “civil rights” until George Clooney in 2006, as he accepted a supporting actor Oscar for “Syriana.” Vanessa Redgrave’s fiery 1978 acceptance speech was the first time a winner said “fascism” or “anti-Semitism.”

Political or social comments were often safely connected to the movie. Celeste Holm, who won best supporting actress in 1948 for “Gentleman’s Agreement,” referred indirectly to the film’s message of religious tolerance. Rod Steiger won best actor in 1968 for the racial drama “In the Heat of the Night” and thanked his co-star, Poitier, for giving him the “knowledge and understanding of prejudice.” The ceremony was held just days after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whose name was never cited by Oscar winners in his lifetime, and Steiger ended by invoking a civil rights anthem: “And we shall overcome.”

Hollywood is liberal-land, but the academy often squirms at political speeches. Redgrave was greeted with boos when she assailed “Zionist hoodlums” while accepting the Oscar for “Julia,” a response to criticism from far-right Jews for narrating a documentary about the Palestinians. She was rebutted the same night: Paddy Chayevsky, giving the award for best screenplay, declared that he was “sick and tired of people exploiting the Academy Awards for the propagation of their own propaganda.”

Producer Bert Schneider and director Peter Davis, collaborators on the 1974 Oscar-winning Vietnam War documentary “Hearts and Minds,” both condemned the war by name (they were the first winners to do so), welcomed North Vietnam’s impending victory and even read a telegram from the Viet Cong. An enraged Bob Hope, an Oscar presenter and longtime Republican, prepared a statement and gave it to Frank Sinatra, who was to introduce the screenplay award: “The academy is saying, ‘We are not responsible for any political references made on the program, and we are sorry they had to take place this evening.’”

In 2003, Michael Moore received a mixed response after his documentary on guns, “Bowling for Columbine,” won for best documentary. The filmmaker ascended the stage to a standing ovation, but the mood soon shifted as he attacked George W. Bush as a “fictitious president” and charged him with sending soldiers to Iraq for “fictitious reasons.” The boos were loud enough for host Steve Martin to joke that “Right now, the Teamsters are helping Michael Moore into the trunk of his limo.”

Sometimes, the academy tries to head off any statements before they’re made. Whoopi Goldberg, host of the 1994 show, hurried out a list of causes during her opening monologue.

“Save the whales. Save the spotted owl. Gay rights. Men’s rights. Women’s rights. Human rights. Feed the homeless. More gun control. Free the Chinese dissidents. Peace in Bosnia. Health care reform. Choose choice. ACT UP. More AIDS research,” she said, before throwing in jokes about Sinatra, Lorena Bobbitt and earthquakes.

The audience laughed and cheered.

Marlon Brando’s full speech below unedited:

For 200 years we have said to the Indian people who are fighting for their land, their life, their families and their right to be free: ”Lay down your arms, my friends, and then we will remain together. Only if you lay down your arms, my friends, can we then talk of peace and come to an agreement which will be good for you.”

When they laid down their arms, we murdered them. We lied to them. We cheated them out of their lands. We starved them into signing fraudulent agreements that we called treaties which we never kept. We turned them into beggars on a continent that gave life for as long as life can remember. And by any interpretation of history, however twisted, we did not do right. We were not lawful nor were we just in what we did. For them, we do not have to restore these people, we do not have to live up to some agreements, because it is given to us by virtue of our power to attack the rights of others, to take their property, to take their lives when they are trying to defend their land and liberty, and to make their virtues a crime and our own vices virtues.

But there is one thing which is beyond the reach of this perversity and that is the tremendous verdict of history. And history will surely judge us. But do we care? What kind of moral schizophrenia is it that allows us to shout at the top of our national voice for all the world to hear that we live up to our commitment when every page of history and when all the thirsty, starving, humiliating days and nights of the last 100 years in the lives of the American Indian contradict that voice?

It would seem that the respect for principle and the love of one’s neighbor have become dysfunctional in this country of ours, and that all we have done, all that we have succeeded in accomplishing with our power is simply annihilating the hopes of the newborn countries in this world, as well as friends and enemies alike, that we’re not humane, and that we do not live up to our agreements.

Perhaps at this moment you are saying to yourself what the hell has all this got to do with the Academy Awards? Why is this woman standing up here, ruining our evening, invading our lives with things that don’t concern us, and that we don’t care about? Wasting our time and money and intruding in our homes.

I think the answer to those unspoken questions is that the motion picture community has been as responsible as any for degrading the Indian and making a mockery of his character, describing his as savage, hostile and evil. It’s hard enough for children to grow up in this world. When Indian children watch television, and they watch films, and when they see their race depicted as they are in films, their minds become injured in ways we can never know.

Recently there have been a few faltering steps to correct this situation, but too faltering and too few, so I, as a member in this profession, do not feel that I can as a citizen of the United States accept an award here tonight. I think awards in this country at this time are inappropriate to be received or given until the condition of the American Indian is drastically altered. If we are not our brother’s keeper, at least let us not be his executioner.

I would have been here tonight to speak to you directly, but I felt that perhaps I could be of better use if I went to Wounded Knee to help forestall in whatever way I can the establishment of a peace which would be dishonorable as long as the rivers shall run and the grass shall grow.

I would hope that those who are listening would not look upon this as a rude intrusion, but as an earnest effort to focus attention on an issue that might very well determine whether or not this country has the right to say from this point forward we believe in the inalienable rights of all people to remain free and independent on lands that have supported their life beyond living memory.

Thank you for your kindness and your courtesy to Miss Littlefeather. Thank you and good night.

This statement was written by Marlon Brando for delivery at the Academy Awards ceremony where Mr. Brando refused an Oscar. The speaker, who read only a part of it, was Shasheen Littlefeather.

The post Marlon Brando was ‘The Godfather’ of Academy Award political speeches appeared first on Movie TV Tech Geeks News By: George Cando