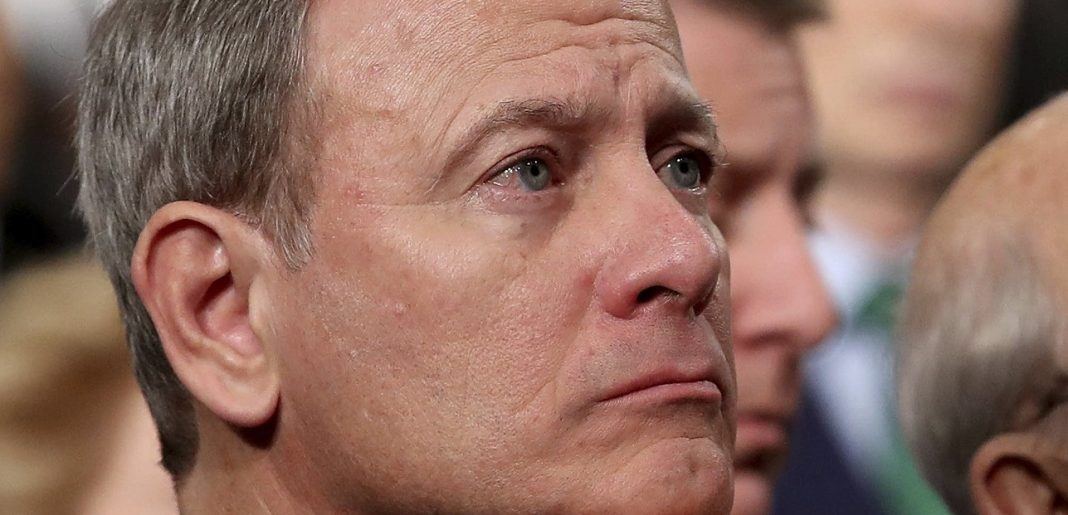

Supreme Court Justice John Roberts will now become a deciding vote on many issues important to both sides of the political spectrum. Now now the Supreme Court is back in session, we’ll soon learn where he stands on several issues that could affect the United States for decades to come.

With a deadline for nearly 30 cases looming and weighty issues of religion, gerrymandering and the 2020 census pending, Chief Justice John Roberts took his black leather chair at the bench this week and said three decisions were ready to be announced.

It was a paltry total for a week in June, the final month of the annual session. What’s more, two of the three were by unanimous votes and none made big headlines.

But the term won’t end this way. And much of the weight of this momentous session is on Roberts’ shoulders.

This is the first time in Roberts’ 14 years as chief justice that he will likely be the deciding vote on several final, tense cases — a total of 24 over the next two weeks. Roberts landed in the ideological center of the court last year when Justice Anthony Kennedy retired after a three-decade tenure. And because Roberts has long been to the right of centrist conservative Kennedy, the court is primed to make a sharp conservative turn.

Last Friday, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the court’s senior liberal, warned of a spate of 5-4 rulings to come and said Kennedy’s retirement would be “of greatest consequence” for pending cases.

While close observers of the court have forecast that for nearly a year, such a prediction is of a different magnitude coming from a justice who has witnessed firsthand the court’s private votes in its closed conference room. Ginsburg knows where the majority is headed.

Two of the most politically charged cases awaiting resolution, testing 2020 census questions and partisan gerrymanders, could lead to decisions favoring Republican Party interests and reinforce the partisan character of a court comprising five GOP appointees and four Democratic ones.

That is a signal Roberts — always insisting the court is a neutral actor — does not want to send, despite past sentiment that would put him on the Republican side in both.

“People need to know that we’re not doing politics,” he said in a February appearance at Belmont University in Nashville. “They need to know that we’re doing something different, that we’re applying the law.”

Conflicts over such interpretations of the law, and the churning environment of the nation’s capital, are no doubt adding to protracted disagreements behind the scenes.

Among the most awaited cases are those testing whether the Trump administration may validly add a citizenship question to the 2020 census; whether judges will be allowed to curtail partisan gerrymanders that make it nearly impossible to unseat the controlling party in a state; and whether a 40-foot cross, a World War I memorial known as the Peace Cross, may remain on public land in Maryland.

Predictions at this stage can be fraught but based on oral arguments and other signs from the justices, the answer to all three questions may be yes. It is certain the nation is headed for more 5-4 rulings. It is also likely that the 64-year-old chief justice, concerned about the place of the high court in these volatile times, will try to neutralize any appearance of politics.

In June 2018, when Roberts wrote the five-justice decision upholding President Donald Trump’s travel ban on nationals from certain majority-Muslim countries, he deferred to the executive and insisted (over a dissent from the four liberals): “This is an act that could have been taken by any other president.”

Decider on the census

June is always arduous as the justices finish opinions in the toughest cases and decide which pending appeals should be scheduled for arguments in the upcoming term, which begins in October.

Roberts has said that he tries to persuade colleagues to decide cases as narrowly as possible, with an opportunity for greater consensus. Some cases defy that goal, sometimes because of the chief justice’s own interest.

In the dispute over a citizenship question on the census, Roberts appeared ready during April oral arguments to accept the government’s assertion that Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross wanted the question added to help the Department of Justice enforce the Voting Rights Act.

The state of New York and Democrat-dominated challengers reject those grounds as contrived and point to Census Bureau analyses that predict such a question would diminish the response rate from noncitizens and Hispanics. That could have consequences for political power and government money across the US. The decennial count is used to apportion seats in the US House and allocate hundreds of billions of dollars in federal and state funds.

Since those April arguments, the American Civil Liberties Union and others that joined the legal challenge against the Trump administration said they had found new evidence that the Commerce Department was trying to help Republicans. They cited a newly disclosed 2015 study written by Dr. Thomas Hofeller, a Republican redistricting expert, that using only the citizen voting-age population for redistricting purposes would be “advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites.”

The Supreme Court has not responded to the revelation, which was relayed to the justices in a letter. But Roberts had made clear, during oral arguments, that he did not believe the justices should consider material that was not part of the earlier lower court record in the case.

In public appearances, Roberts has downplayed his role at the helm of the nation’s top court. “There have been 17 chief justices, and I’d be very surprised if people in here could name” them, he said at Belmont University. “My point is that you’re not guaranteed to play a significant role in the history of your country, and it’s not necessarily a bad thing if you don’t.”

But now he is not only in the center chair, presiding. He is also positioned to decide the outcome of cases. It is not yet known how he will balance his institutional and ideological interests.

Supreme Court justices can be inscrutable, and on Monday, nothing in Roberts’ nor his colleagues’ courtroom demeanor revealed what to expect between June 17 (when the nine are scheduled to return to the bench) and the end of the month.

In her New York speech last Friday, Ginsburg intimated that the court was about to drop a series of contentious decisions, and that the absence of Kennedy’s steadying influence would be consequential.

Ginsburg pointed to comparisons between the census dispute and last term’s “travel ban” case.

She referred to the deference that the Roberts majority had shown the Trump administration in the latter and closed her discussion of the former with this observation: The challengers “in the census case have argued that a ruling in Secretary Ross’s favor would stretch deference beyond the breaking point.”

What to read into Ginsburg’s speech? Irrespective of whether she intended it, Ginsburg has a reputation for dropping sly hints outside the courtroom.

In mid-June 2012, she said in a speech that, “The term has been more than usually taxing.” That was just before a narrow majority of justices, with Roberts casting the deciding vote, upheld the Affordable Care Act based on the surprising rationale of congressional taxing power.

Supreme Court Frequently Asked Questions

As of October 2018, there have been 114 Justices.

The average number of years that Justices have served is 16.

The longest-serving Chief Justice was Chief Justice John Marshall who served for 34 years, 5 months and 11 days from 1801 to 1835.

The shortest serving Chief Justice was John Rutledge who was appointed under a temporary commission because the Senate was in recess. He served for 5 months and 14 days before the Senate reconvened and rejected his nomination.

The longest-serving Justice was William O. Douglas who served for 36 years, 7 months, and 8 days from 1939 to 1975.

John Rutledge served the shortest tenure as an Associate Justice at one year and 18 days, from 1790 to 1791. The next shortest tenure was that of James F. Byrnes who served 1 year, 2 months, and 25 days from 1941 to 1942. For many years, Justice Thomas Johnson was thought to have been the shortest serving Justice but under a temporary recess appointment he served a total of 1 year, 3 months and 28 days.

John Jay (1789-1795) was 44 years old when he took his oath of office.

Harlan F. Stone (1941-1946) was 68 years old when he took his oath of office.

Horace Lurton (1910-1914) was 65 years old when he took his oath of office. Who was the oldest Associate Justice?

The oldest person to serve as a Supreme Court Justice was Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., (1902-1932) who was 90 when he retired from the Court.

Six Justices were born outside the United States. They are:

James Wilson (1789-1798) born in Caskardy, Scotland

James Iredell (1790-1799) born in Lewes, England

William Paterson (1793-1806) born in County Antrim, Ireland

David J. Brewer (1889-1910) born in Smyrna, Turkey

George Sutherland (1922-1939) born in Buckinghamshire, England

Felix Frankfurter (1939-1962) born in Vienna, Austria

William Howard Taft is the only person to have served as both President of the United States (1909-1913) and Chief Justice of the United States (1921-1930).

Associate Justice Louis D. Brandeis (1916-1939).

Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall (1967-1991).

Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor (2009-Present).

Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (1981-2006).

Two Associate Justices were named John Marshall Harlan. The first served from 1877 to 1911. The second, his grandson, served from 1955 to 1971.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. – Harvard (J.D.)

Justice Clarence Thomas – Yale (J.D.)

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg – Columbia (LL.B)

Justice Stephen G. Breyer – Harvard (LL.B)

Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. – Yale (J.D.)

Justice Sonia Sotomayor – Yale (J.D.)

Justice Elena Kagan – Harvard (J.D.)

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch – Harvard (J.D.)

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh – Yale (J.D.)

Judicial robes have long been thought to bring dignity and solemnity to judicial proceedings. Following the custom of English judges, some American colonial judges adopted the wearing of robes along with many other customs and principles of the English common law system. When the Supreme Court first met in 1790, the Justices had not settled on whether to wear robes, but in February 1792 they did appear in a standard set of robes for the first time, which one reporter referred to as “robes of justice.” These robes are thought to have been black, trimmed with red and white on the front and sleeves. They were only used for a few years before the Justices adopted all black robes.